BONE MASS 101: The ultimate guide to bone mass

and maximising bone growth

INTRODUCTION

Bone mass is very important for your health, strength, and of course, appearance. Strong developed bones give support for muscles, posture, and movement, and affect your facial structure and body proportions. Genetics do play a big part in bone size and density, but they do not firmly limit your potential. Bone is a living tissue, so it is constantly responding to the environment it is in.

Nutrition, physical activity, hormones, sleep, and your lifestyle affect how much bone is built, maintained, or lost. You need to understand this if you want to increase bone mass naturally, instead of relying on risky drugs and peptides.

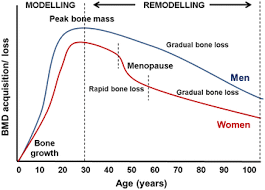

Development of the bone involves some processes: growth, modeling, and remodeling. In childhood and teenage years, bones will grow in length and thickness as the body matures and approaches peak bone mass. So, this period will be key for maxxing your bone mass. In adulthood, while bones cannot grow in length, they can still be responsive to mechanical stress and signals from the body. In remodeling, bone tissue breaks down and rebuilds, increasing density and strength when conditions are made right.

Lifestyle choices can significantly affect bone quality even after maturity, so it is never too late to make a difference.

I am studying biology at the moment, so I thought I could come on this forum and make a biology-backed guide on what works and what doesn't, hope you like

CHAPTER 1: BONE BIOLOGY AND PHYSIOLOGY

Bone is a dynamic, metabolically active tissue, not just an inert material. Its strength and function come from both its composition and internal organisation. Bone exists in two primary forms, each serving a distinct role in the skeleton.

- Cortical bone forms the dense outer layer of most bones. It makes up the majority of bone mass and is responsible for strength, rigidity, and resistance to bending and twisting. Cortical bone adapts slowly but provides long-term structural stability, especially in weight-bearing areas like the femur, tibia, and spine.

- Trabecular bone is located at the ends of long bones and inside vertebrae. It has a lattice-like structure that allows it to absorb shock and respond quickly to mechanical and hormonal changes. Although it contributes less to overall mass, trabecular bone is very metabolically active and is often the first area where changes in bone density are noticed.

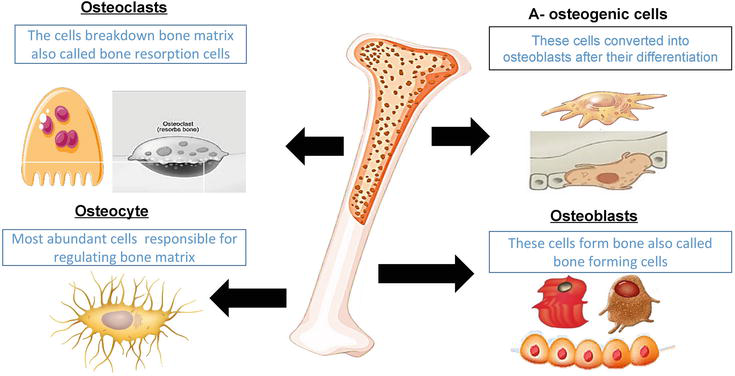

- Osteoblasts are the bone-forming cells that create new bone tissue. They synthesize the organic bone matrix, mainly made of type I collagen, and start the deposition of minerals like calcium and phosphorus. When bone formation is favored, osteoblast activity exceeds bone breakdown, leading to increased bone mass and density.

- Osteoclasts are large cells that break down and absorb bone tissue. This process releases minerals into the bloodstream and allows old or damaged bone to be replaced. Osteoclast activity is essential for bone renewal and mineral balance. Problems occur only when breakdown exceeds formation over time.

- Osteocytes are mature bone cells embedded in the bone matrix. They are primary sensors of mechanical stress, detecting loading patterns and signaling where bone should be strengthened or weakened. Through chemical signals, osteocytes coordinate the work of osteoblasts and osteoclasts, making them key regulators of bone adaptation to exercise and daily movement.

- One of the central regulators is Wnt/β-catenin signaling. This pathway promotes osteoblast differentiation, survival, and activity, while subtly suppressing osteoclast activity through increased osteoprotegerin (a decoy cell blocking bone breakdown) expression. Osteocytes help modulate this pathway by producing sclerostin, which inhibits Wnt signaling under conditions like low mechanical load or energy stress, thereby reducing bone formation when demand is low.

- CCN3 (NOV) acts as another local brake on bone formation, limiting osteoblast growth and matrix production to tightly regulate bone accumulation during development and remodeling. Together, these regulators integrate local mechanical stress, cellular maturity, and metabolic context to decide when bone formation should be allowed, restricted, or actively limited. This reinforces that skeletal mass is tightly controlled by signaling within the tissue rather than unrestricted responses to outside stimuli.

The alkaline regulation of bone remodeling refers to the local alkaline microenvironment created by osteoblasts during matrix mineralization, mostly through alkaline phosphatase activity. Alkaline phosphatase breaks down inorganic pyrophosphate, a strong inhibitor of mineral deposition, increasing local phosphate availability and allowing hydroxyapatite crystals to form within the collagen matrix. This process happens at the osteoid surface and is tightly controlled in space, enabling mineralization without changing overall blood pH. Disruption of alkaline phosphatase activity, as seen in hypophosphatasia, can lead to poor mineralization despite adequate calcium and phosphate, thus, bone formation relies on precise enzyme control rather than general alkalinity.

This tells us that claims suggesting dietary "alkalization" can directly improve bone mineralization confuse systemic acid-base balance with the specific biochemical environment in bone tissue. Blood pH is strictly regulated within a narrow range, and dietary choices do not largely alter the alkaline microenvironment needed for mineral deposition at the osteoid surface.

So, claims that eating more "alkaline foods" like cucumbers, lemon water, spinach, potatoes, and bananas will enhance this process are FALSE.

Oxytocin is gaining recognition here, as I have seen, as a local and systemic regulator of bone remodeling, acting on osteoblasts and osteoclasts through specific receptors in bone tissue. Experimental studies show that oxytocin encourages osteoblast differentiation and activity while reducing excessive osteoclast-driven bone breakdown, promoting bone formation under certain conditions.

Its skeletal effects work independently of sex hormones and may interact with estrogen signaling, helping explain the different ways in which bone is regulated in males and females. But oxytocin's effects depend heavily on the context and typically operate within normal reproductive, metabolic, and neuroendocrine states. It does not drive unusually high bone growth. Oxytocin serves as a fine-tuning hormone in maintaining skeletal balance, not a main factor in determining bone mass or a viable target for boosting it.

Lifestyle choices that temporarily increase oxytocin release, like social bonding or touch, do not create significant increases in bone mass.

Fibroblast Growth Factor Receptor 3 (FGFR3) is a key negative regulator of longitudinal bone growth. It acts at the growth plate during endochondral ossification, the process where cartilage is gradually replaced by bone. FGFR3 activation slows chondrocyte (cells which are embedded in the matrix of cartilage) growth and maturation by inhibiting specific signaling pathways. This braking system is important for coordinated skeletal development, preventing excessive or disorganised growth. Gain-of-function mutations in FGFR3 lead to conditions like achondroplasia, where early growth plate inhibition results in shorter limb length despite normal bone mineralization. It's important to note that FGFR3 activity is limited to developmental stages; once growth plates close, its effect on bone length is minimal.

Bone turnover is also controlled by hormones that affect the balance between formation and breakdown. Growth hormone (GH) and insulin-like growth factor 1 (IGF-1) boost bone formation, especially during periods of growth and recovery.

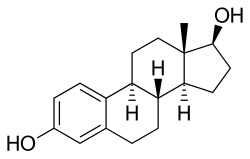

Sex hormones, like testosterone and estrogen, are essential for maintaining bone density by supporting osteoblast activity and keeping excessive osteoclast activity in check.

Vitamin D and parathyroid hormone regulate calcium availability to ensure enough minerals are present for bone mineralization while maintaining stable blood calcium levels. Conversely, long-term high cortisol levels increase bone breakdown and suppress formation, so it is very important it is to manage stress and ensure adequate recovery.

CHAPTER 2: WINDOWS FOR ACCRUAL

Bone mass does not accumulate evenly throughout life. It follows a specific pattern where certain periods are more important than others. Childhood and teenage years are super big for skeletal development, as bone size and density increase rapidly during these times. In childhood, bone growth supports body expansion, while the coordination between muscle force and skeletal strength improves over time.

The teenage years see the biggest increase in bone mass, driven mainly by hormonal changes in puberty. Growth hormone, IGF-1, and rising sex hormone levels boost bone formation, allowing the skeleton to thicken, lengthen, and strengthen in prep for adulthood.

Peak bone mass is usually reached in the late teens to mid-twenties, but this timing varies by sex, genetics, and lifestyle. Achieving a high peak bone mass is one of the best indicators of skeletal health, as it determines the amount of "reserve" before age-related bone loss begins. Poor nutrition, low energy availability, or lack of mechanical loading during these years can permanently limit max bone density, even if healthy habits are adopted later on.

On the other hand, adequate protein, minerals, resistance training, and weight-bearing activities during this time can increase peak bone mass beyond genetic averages.

Bone length growth occurs because of growth plates, which are areas of cartilage near the ends of long bones. These plates allow bones to lengthen during development and close as puberty progresses. Once the growth plates fuse, further increases in bone length are impossible.

However, the timing of closure varies among bones. Bones like those in the hands, feet, and face tend to mature and fuse early, often during the mid-teen years.

In contrast, some bones continue developing for a longer time. The clavicle is a notable example, as it is one of the last bones to fully mature, with growth and fusion continuing into the early to mid-twenties.

After skeletal maturity, bones maintain a considerable degree of flexibility, even though they can no longer grow in length. Bones can still increase in thickness, density, and internal strength through modeling and remodeling. Mechanical loading, especially from resistance training and weight-bearing activities, can stimulate periosteal expansion and improve bone geometry, increasing strength without changing height.

Trabecular bone is especially responsive to training and hormonal signals, allowing improvements in bone quality well into adulthood. While the potential for change is less than in childhood and teenhood, consistent lifestyle choices can still maintain and even enhance bone mass after maturity.

CHAPTER 3: GENETICS

Bone density and skeletal structure are greatly influenced by genetics, with heritability estimates for bone mineral density often ranging from moderate to high. Genetic factors help determine baseline traits such as bone size, shape, cortical thickness, and overall potential for peak bone mass. Differences in genes involved in collagen production, vitamin D metabolism, calcium transport, and hormonal signaling all contribute to individual variations in skeletal strength.

These inherited factors explain why some people naturally develop denser or broader bones than others, even under similar environmental conditions. Genetics only set you a range of possibilities, not a set outcome.

Epigenetics describes how environmental factors can change gene expression without altering the DNA sequence itself. In the context of bone health, this regulation is heavily influenced by nutrition, mechanical loading, and hormone levels.

Adequate intake of protein and minerals can boost the expression of genes involved in bone formation, while resistance training and weight-bearing activities activate pathways that promote bone-building cells. Hormonal signals such as growth hormone, testosterone, and estrogen further influence how genes related to bone turnover are expressed.

Conversely, chronic undernutrition, lack of activity, or prolonged stress can suppress the processes that encourage bone formation and shift metabolism toward bone breakdown. Through these mechanisms, lifestyle choices affect where someone falls within their genetic potential for bone mass.

Bone development is also influenced by early-life conditions, where factors during prenatal development, infancy, and childhood have lasting effects on skeletal health. Maternal nutrition, vitamin D levels, and overall energy availability impact fetal bone formation and mineralization. In early childhood, a good diet and physical activity help create favorable epigenetic patterns that support long-term bone strength.

There is evidence that some of these epigenetic changes may carry over to future generations, suggesting that the nutritional and hormonal environment experienced by parents can shape skeletal outcomes in their children.

CHAPTER 4: WOLFF'S LAW

Wolff’s Law explains how bone adjusts to the mechanical forces applied to it. When a bone regularly bears weight, it grows stronger and denser in the directions needed to handle that stress. On the other hand, when mechanical stress decreases, such as during long periods of inactivity, bone mass drops.

This ability to adapt helps the skeleton stay efficient by building bone only when necessary. Mechanical loading serves as one of the strongest natural regulators of bone mass, working independently and together with nutrition and hormones.

On a cellular level, this adaptation happens through mechanotransduction, a process that converts mechanical forces into biological signals. Osteocytes, which are embedded in the bone matrix, sense strain, fluid movement, and deformation from loading. These cells then communicate with osteoblasts and osteoclasts to regulate bone formation and breakdown. High-strain, dynamic loading activates pathways that promote bone growth, while low-level or static forces have minimal impact. This is why bones respond best to varied and intermittent loading rather than constant, low-intensity stress.

Beyond load magnitude alone, bone is very sensitive to strain rate, with rapid, high-velocity forces like jumping, sprinting, or explosive lifts producing a stronger osteogenic signal than slow and static loading at the same force.

Different types of physical activity apply unique loads to the skeleton. Resistance training creates high mechanical tension on bones through muscle contractions, especially at attachment points. This makes it highly effective for enhancing cortical thickness and overall bone strength. Impact loading from activities like jumping or sprinting generates rapid force transmission that strongly affects trabecular bone, particularly in the hips and spine.

Axial compression, where force travels along the bone length, occurs in exercises like squats or loaded carries and helps reinforce weight-bearing areas.

The effectiveness of mechanical loading depends a lot on how exercise is designed. Intensity is key since bones respond best to loads that are higher than their usual levels. Applying greater forces is more beneficial for bone growth than frequently applying low-level stress, although you should do this safely.

The frequency of exercise should encourage repeated stimulation, but not be so high that it hampers recovery. Rest is important because bone formation takes place during recovery, not during the load itself. Gradual progression keeps bones adapting by slowly increasing the load or complexity to avoid plateaus. Short, intense, well-timed loading sessions usually work better for bone health than long, repetitive endurance training.

Bone cells rapidly desensitise to continuous mechanical loading, a phenomenon known as mechanoadaptation. Short rest intervals between loading, anywhere from minutes to several hours, restore osteocyte sensitivity and amplify bone formation signals.

A separate discussion in Wolff's law is bonesmashing, which involves deliberately striking bones to promote adaptation and growth. While mechanical stress does impact bone remodeling, inflicting direct blunt trauma does not mimic the controlled loading seen in resistance training. Instead, it poses risks like microfractures, asymmetry, inflammation, and long-term structural weakness if healing is disorganised.

Bone adaptation depends on strain patterns created by muscle force and ground reaction forces, not from repeated injuries by hitting your face with a hammer. There is no evidence that intentional bone striking safely boosts bone mass beyond what progressive mechanical loading can achieve. And from a biological viewpoint, structured resistance and impact training provide the stimulus that bones evolved to respond to, while repeated trauma raises injury risks without offering better benefits.

TLDR: Bonesmashing does not work.

CHAPTER 5: MACRONUTRIENTS

Macronutrients provide both the structural building blocks and the signals needed for bone formation. While minerals like calcium and phosphorus are important, bone mass cannot reach its full potential without enough protein, carbohydrates, and fats to support cellular activity and hormonal balance.

Protein and amino acid signalling

Protein is big for building bone matrix since bones form on a collagen scaffold before mineralization. Getting enough protein activates several pathways that increase bone mass:

- mTOR signaling: Triggered by essential amino acids, especially leucine. mTOR supports osteoblast growth and protein production, including collagen. It works best with adequate total protein intake spread across meals, particularly from sources like dairy, eggs, meat, and whey.

- IGF-1 production: Eating protein raises the levels of IGF-1, a vital hormone for bone growth and density. IGF-1 boosts osteoblast activity and helps with growth during development as well as bone formation during remodeling. Both energy and enough protein are necessary.

- Collagen synthesis: Amino acids like glycine, proline, and lysine are required to make type I collagen, which affects bone toughness and fracture resistance. This is supported by gelatin, dairy, meat, and vitamin C.

- Calcium absorption support: Higher protein intake boosts calcium absorption in the intestines and encourages calcium conservation by the kidneys when energy intake is sufficient.

- Muscle-bone interaction: Protein helps with muscle growth, which increases mechanical loading on bones. Stronger muscles apply greater forces at bone attachment sites, leading to bone formation through mechanotransduction.

- Osteoblast differentiation: Amino acids affect the gene expression necessary for osteoblast maturation, promoting bone formation over breakdown.

The best protein sources include eggs, chicken breast, lean beef, dairy, and fatty fish.

Carbohydrates, insulin, and bone anabolism

Carbohydrates support bone indirectly by ensuring energy availability and balancing anabolic hormones. Enough carbohydrate intake stimulates insulin secretion, which benefits bone. Insulin encourages osteoblast activity and enhances IGF-1 signaling, creating a good environment for bone formation. Carbs also lower cortisol levels by preventing chronic energy deficits, which can speed up bone loss.

Sufficient glycogen improves training quality and loading intensity, further stimulating bones. Diets that are low in carbohydrates, especially combined with high training volumes, can lower bone turnover by suppressing anabolic hormones and increasing stress signals.

Dietary fats and steroid hormone synthesis

Dietary fats are important for producing steroid hormones that manage bone metabolism, especially testosterone and estrogen. These hormones limit excessive bone loss and support osteoblast survival. Fats also help absorb vitamins that are great for bone health, such as vitamin D and K. Dairy foods are important here because they provide a blend of fats, protein, minerals, and bioactive compounds.

Some options include whole milk, Greek or fermented yogurt, eggs (esp. the yolks), fatty fish, aged or full-fat cheeses, moderate amounts of butter or cream, olive oil, nuts, seeds, and kefir.

Getting enough fat helps maintain hormonal balance, supports vitamin absorption, and ensures that bone turnover remains even rather than skewed toward loss. Very low-fat diets can disrupt these processes, especially during youth and early adulthood when hormonal signals matter greatly.

CHAPTER 6: MICRONUTRIENTS

Micronutrients regulate bone mineralisation, structural integrity, and turnover efficiency. While macronutrients provide energy and building blocks, micronutrients determine whether bone tissue is properly formed, mineralised, and maintained. Deficiencies do not just simply slow progress but can actively impair bone quality and increase fragility, even when calories and protein are sufficient.

Calcium and phosphorus balance

Calcium and phosphorus are the primary mineral components of bone, forming hydroxyapatite crystals that give bone its hardness and compressive strength. These minerals must be present in the correct ratio to allow proper mineral deposition. Calcium will provide rigidity and resistance to compression, and phosphorus stabilises bone mineral structure.

Adequate intake of both in the right ratio supports peak bone mass and fracture resistance. Deficiency in calcium increases parathyroid hormone release, and accelerating bone resorption, while phosphorus deficiency impairs mineralisation and reduces bone strength. Chronic imbalance can lead to porous or poorly mineralised bone.

Good sources of both are: Dairy (milk, yogurt, cheese), small fish with bones, eggs, meat and poultry, whole grains, and legumes.

Vitamin D

Vitamin D regulates calcium and phosphorus absorption and directly influences bone cell activity. Without adequate vitamin D, dietary calcium cannot be efficiently incorporated into bone. Vitamin D increases intestinal calcium and phosphorus absorption, supports osteoblast function, and reduces excessive parathyroid hormone activity. Deficiency in vitamin D reduces calcium absorption regardless of intake, increases bone resorption, and increases fracture risk and impaired bone mineral density.

Good sources of vitamin D are: Sunlight, cod liver oil, oily fish (rainbow trout, oil-canned sardines, salmon), UV-exposed mushrooms, and fortified foods.

Vitamin K2

Vitamin K2 directs calcium into bone tissue and away from soft tissues. It activates proteins involved in bone mineralisation, particularly osteocalcin. Vitamin K2 ensures calcium is deposited into bone rather than arteries, improves bone quality, density and strength, and supports bone matrix maturation, while a deficiency in vitamin K2 worsens calcium utilisation, increases risk of soft tissue calcification, and reduces bone quality despite adequate calcium intake.

Good sources of vitamin K2 are: Aged cheeses, fermented dairy, and egg yolks.

Magnesium

Magnesium is required for bone crystal formation, vitamin D activation, and regulation of parathyroid hormone. Magnesium stabilises bone mineral structure, enhances vitamin D metabolism, and supports normal bone turnover. A deficiency in magnesium causes impaired calcium utilisation, increases bone fragility, and disrupts hormonal regulation of bone metabolism.

Good sources of magnesium are: Nuts and seeds, whole grains, dairy products, and leafy vegetables.

Trace minerals

Zinc

Zinc is involved in bone growth, osteoblast differentiation, and collagen synthesis. Zinc stimulates osteoblast activity, supports collagen formation, and enhances growth-related bone signalling. A deficiency in zinc causes Impaired skeletal growth, reduced bone formation, and lower bone mineral density (BMD).

Zinc

Good sources of zinc are: Meat, dairy products (esp. cheese), eggs, shellfish, and whole grains.

Boron

Boron influences bone metabolism by modulating hormone activity and mineral retention. Boron improves calcium and magnesium utilisation, supports steroid hormone activity, and enhances BMD, while deficiency can cause increased calcium loss, reduced bone strength, and impaired hormonal regulation of bone.

Good sources of boron are: Fruits (esp. apples and prunes) and nuts.

Other important trace minerals

Some additional trace minerals support bone integrity and structure. Here are a few that are important to know:

- Copper: Needed for collagen cross-linking. Deficiency weakens bone matrix and increases fracture risk. Found in nuts, seeds, and whole foods.

- Manganese: Involved in bone formation enzymes. Deficiency impairs skeletal development. Found in whole grains and nuts.

- Silicon: Supports connective tissue and early bone mineralisation. Found in whole grains and some plant foods.

- Iron: supports bone health indirectly by enabling collagen-synthesising enzymes and osteoblast energy metabolism. Deficiency impairs bone quality, but excess iron promotes oxidative stress and bone loss. Found in red meat, liver, and eggs (esp. the yolks).

Nitric oxide signalling

Dietary nitrates function as bioactive compounds that support bone health indirectly through nitric oxide signalling rather than by providing structural substrate. Nitrates from foods such as beetroot juice, arugula, spinach, rocket, celery, and pomegranate are reduced to nitrite and subsequently to nitric oxide, a signalling molecule produced locally within bone by endothelial cells (the lining of blood cells), osteoblasts, and osteocytes.

Nitric oxide enhances skeletal blood flow, improves oxygen and nutrient delivery to active bone tissue, and modulates bone turnover by supporting osteoblast activity while limiting excessive osteoclast-lead resorption. While great nitrate intake can optimise the efficiency of bone remodelling, its effects are permissive and context-dependent, so it is a good thing to implement, but cannot improve bone mass on it's own without nutrition and mechanical load.

The "Primal diet"

The primal diet, focusing on raw meats, raw dairy, raw eggs, and natural raw fats, is sometimes thought to enhance bone health by providing minimally processed, nutrient-dense foods that preserve heat-sensitive vitamins and enzymes.

- Protein & amino acids: Raw meats and eggs supply complete proteins and collagen precursors.

- Calcium & phosphorus: Raw dairy and bones (if consumed) support mineral deposition in bone.

- Magnesium & potassium: Found in raw plant foods included in some variations of the diet, aiding bone density and acid-base balance.

- Vitamin D & K2: Raw dairy and certain animal fats provide fat-soluble vitamins critical for calcium regulation and osteocalcin activation.

- Trace elements: Zinc, copper, boron, and manganese in raw meats and dairy contribute to enzymatic bone formation processes.

- Healthy fats: Natural animal fats offer energy and support fat-soluble vitamin absorption.

CHAPTER 7: COLLAGEN MATRIX AND BONE QUALITY

Bone strength is determined not only by how much mineral it contains, but by the quality of its collagen framework. Before calcium and phosphorus are deposited, bone is laid down as an organic matrix composed mostly of collagen. This matrix provides flexibility, strength, and resistance to cracking. Without a well-formed collagen network, bone may appear dense but remain brittle, increasing fracture risk under real-world stress.

Type I collagen accounts for roughly 90% of the organic component of bone. It forms a fibrous scaffold upon which mineral crystals are deposited in an organised manner. Osteoblasts synthesise collagen fibres, which are then cross-linked and aligned to create a resilient structure capable of withstanding both compression and tension.

Proper collagen synthesis allows bone to absorb force and distribute stress, reducing the likelihood of failure. Disruptions in collagen production or structure impair bone quality even if mineral density appears good.

Several nutrients are essential for effective collagen synthesis and stabilisation.

- Vitamin C is required for the hydroxylation of collagen molecules, a process necessary for proper fibre formation and strength. Deficiency leads to weak, poorly organised collagen and compromised bone integrity. Vitamin C is found in guavas, red bell peppers, orange juice, oranges, and kiwis.

- Copper plays a big role in collagen cross-linking, which stabilises the matrix and increases tensile strength. Copper is found in beef liver, oysters, sesame seeds, and dark chocolate.

- Glycine and proline are amino acids that make up a big proportion of collagen’s structure and must be supplied through adequate protein intake. Good sources of both are gelatin, bone broth, and animal skins (pork, chicken).

The distinction between bone strength and bone density is also important to know. Bone density measures mineral content, but does not fully display how well bone can resist bending, twisting, or impact. Bone strength depends on a combination of density, collagen quality, and bone geometry.

A skeleton with slightly lower mineral density but a robust collagen matrix and good structure may be more resistant to fracture than a denser but brittle one.

CHAPTER 8: HORMONAL OPTIMISATION

Hormones act as master regulators of bone metabolism, determining whether bone tissue is built, maintained, or broken down. While genetics influence baseline hormone levels, lifestyle factors like nutrition, training, sleep, and stress strongly affect hormonal signalling.

Testosterone and oestrogen play central roles in bone mineralisation in both males and females.

Testosterone stimulates osteoblast activity directly and indirectly through conversion to oestrogen, which is essential for maintaining bone density. Oestrogen suppresses excessive osteoclast activity, preventing rapid bone breakdown and preserving trabecular structure, particularly in the spine and hips. Insufficient energy intake, very low body fat, or excessive training volume can suppress these hormones, leading to reduced bone formation and increased fracture risk.

Growth hormone (GH) is a major driver of bone growth and remodelling, largely through its stimulation of IGF-1. Growth hormone secretion follows a pulsatile pattern and is highest during deep sleep. Sleep architecture, particularly the amount of slow-wave sleep, directly influences how much growth hormone is released.

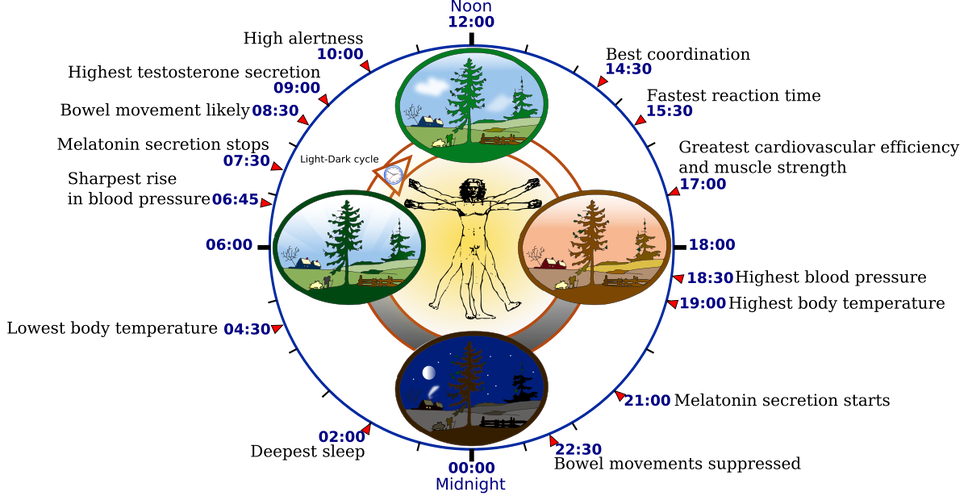

Short sleep duration, irregular sleep schedules, or frequent nighttime disruptions reduce growth hormone output and impair bone formation. Consistent sleep timing (10-11 PM_, sufficient total sleep (8-9 hours), and alignment with natural circadian rhythms support GH secretion and boost the bone’s ability to respond to mechanical loading and nutrition.

Cortisol acts as the opposition to anabolic hormones when chronically elevated. While short-term cortisol release is a normal stress response, prolonged psychological stress, sleep deprivation, or excessive endurance training increases baseline cortisol levels.

Elevated cortisol promotes bone resorption by increasing osteoclast activity and suppressing osteoblast function. It also interferes with calcium metabolism and reduces the effectiveness of growth hormone and sex hormones. Managing stress through adequate recovery, balanced training volume, proper nutrition, and regular sleep is therefore very important for preserving bone mass.

Parathyroid hormone exerts dual effects on bone, with chronic elevation boosting resorption, while brief, pulsatile increases driven by exercise, fasting, and circadian rhythm preferentially stimulate osteoblast activity and bone formation.

Hormonal optimisation is not achieved through isolated interventions, but through a stable lifestyle that supports anabolic signalling while minimising chronic catabolic stress.

CHAPTER 9: GUT HEALTH AND MINERAL ABSORPTION

The gastrointestinal system plays a great role in bone health by determining how effectively nutrients are absorbed and utilised. Even with an optimal diet, poor gut function can severely halt mineral availability and disrupt hormonal signalling involved in bone turnover.

Calcium and magnesium absorption occurs in the small intestine and is tightly regulated by vitamin D, gut acidity, and intestinal integrity. Calcium is absorbed through both active, vitamin D–dependent transport and passive diffusion, with efficiency increasing when intake is spread across meals rather than in one go.

Magnesium absorption depends on similar transport mechanisms and is sensitive to intestinal health and dietary composition. Low stomach acidity, chronic digestive stress, or nutrient imbalances can reduce absorption of both, slowing bone mineralisation even when intake looks fine. Adequate vitamin D status and a well-functioning intestinal lining are pretty much as important as calcium and magnesium intake for effective mineral uptake.

The gut microbiota adds to bone health through its production of short-chain fatty acids, like acetate, propionate, and butyrate, which are generated when gut bacteria ferment dietary fibres and certain carbohydrates. These compounds boost mineral absorption by improving intestinal barrier function and modulating calcium transport. Short-chain fatty acids also influence bone metabolism indirectly by reducing systemic inflammation and supporting regulatory immune signalling that favours osteoblast activity.

A diverse and stable microbiota is supported by whole foods and fermented products.

Chronic inflammation and increased gut permeability negatively affect bone health by disrupting nutrient absorption and increasing bone resorption signals. Inflammatory cytokines stimulate osteoclast activity and suppress osteoblast function, shifting bone turnover toward loss.

Increased gut permeability allows inflammatory compounds to enter circulation, further amplifying this effect. Diets high in ultra-processed foods, prolonged stress, or unresolved digestive issues can contribute to this inflammatory state. Maintaining gut integrity through adequate nutrition, stress management, and dietary diversity supports efficient mineral absorption and helps preserve a hormonal and immune environment conducive to bone growth and maintenance.

Chronic low-grade inflammation elevates cytokines such as interleukin-6 (IL-6) and tumour necrosis factor-alpha (TNF-α), which stimulate osteoclast differentiation and bone resorption. Increased gut permeability amplifies this process by letting endotoxins enter circulation.

CHAPTER 10: SUNLIGHT AND THE CIRCADIAN RHYTHM

Sunlight and circadian rhythms powerful effects on bone metabolism by influencing vitamin D production, hormonal secretion, and the timing of bone turnover processes.

Ultraviolet B radiation from sunlight triggers vitamin D synthesis in the skin, initiating a pathway essential for calcium and phosphorus absorption. Enough UV exposure allows the body to produce vitamin D in regulated amounts, supporting mineral availability and osteoblast function.

Insufficient sunlight exposure reduces vitamin D synthesis, impairing calcium absorption and increasing parathyroid hormone activity, which speeds up bone resorption. Factors such as latitude, season, skin coverage, and time spent outdoors strongly influence vitamin D status, making sunlight a top environmental determinant of bone health.

Bone turnover follows circadian rhythms, with predictable daily fluctuations in bone formation and resorption. Hormones that regulate bone metabolism, like cortisol, GH, and melatonin, are under circadian control. Bone resorption increases during the night, while bone formation is more active during the day when mechanical loading and nutrient intake occur.

Disruption of circadian rhythms through irregular sleep schedules, late-night light exposure, or shift work alters this balance, increasing resorption and reducing formation. Consistent sleep timing, daytime light exposure, and nighttime darkness help maintain a circadian environment that maintains bone preservation and adaptation.

Bone metabolism also has seasonal variation, driven by changes in sunlight exposure, physical activity, and vitamin D status. Bone mineral density (BMD) increases during sunnier months when vitamin D synthesis and outdoor activity are higher, and decline during darker seasons when these are reduced. Seasonal drops in vitamin D are associated with increased parathyroid hormone activity and bone resorption. Maintaining regular outdoor exposure, physical activity, and nutritional support throughout the year helps reduce these seasonal fluctuations.

CHAPTER 11: BODY COMPOSITION AND ENERGY

Body composition and energy availability strongly influence bone density by regulating mechanical loading, hormonal signalling, and metabolic stability. Bone adapts not only to external forces but also to the internal environment created by muscle mass and energy intake.

Lean mass is one of the greatest predictors of bone density. Skeletal muscle applies force to bone during movement and resistance training, stimulating bone formation through mechanotransduction. Greater lean mass increases both the magnitude and frequency of these forces, particularly at muscle attachment sites, leading to thicker cortical bone and improved bone geometry.

This muscle–bone interaction is very important during growth and early adulthood, when increases in muscle size and strength strongly influence peak bone mass. Loss of lean mass, whether through inactivity, undernutrition, or ageing, reduces mechanical loading and accelerates bone loss.

Low energy availability occurs when caloric intake is insufficient to support the demands of basal metabolism, physical activity, and physiological processes like bone turnover. In this state, the body prioritises short-term survival over tissue building. Hormonal adaptations include reductions in testosterone, oestrogen, GH signalling, and IGF-1, alongside increases in cortisol. These changes suppress osteoblast activity and boost bone resorption, leading to gradual declines in bone density even in individuals who continue to train. Importantly, mineral intake alone cannot offset the bone loss caused by chronic energy deficiency.

Relative Energy Deficiency in Sport (RED-S) is a clinical condition in which prolonged low energy availability impairs multiple physiological systems, including bone health. RED-S is associated with decreased bone formation, increased fracture risk, and failure to reach or maintain peak bone mass. While commonly discussed in endurance athletes, it can occur in anybody engaging in high training volumes without adequate energy intake. Prevention requires aligning caloric intake with training demands, maintaining sufficient body fat for hormonal function, and allowing time for good recovery.

CHAPTER 12: FACTORS LIMITING YOUR BONE GROWTH

Bone mass is super sensitive to negative environmental and behavioural factors that disrupt hormonal balance, nutrient usage, and mechanical stimulation. Even with fine nutrition and exercise, these influences can limit bone growth or accelerate bone loss.

Smoking reduces blood supply to bone tissue, suppresses osteoblast activity, and interferes with oestrogen and testosterone signalling, leading to reduced bone formation and slower fracture healing.

Alcohol, particularly when consumed chronically or in large amounts, inhibits osteoblast function and increases cortisol levels, promoting bone resorption.

Both substances disrupt vitamin D metabolism and calcium absorption, compounding their negative effects on bone density. Long-term exposure increases fracture risk and reduces peak bone mass, especially when initiated during adolescence or early adulthood.

Ultra-processed foods can undermine bone health by displacing nutrient-dense foods and introducing compounds that interfere with mineral balance. High sodium intake increases calcium loss in your piss, while excessive refined sugars and some food additives promote systemic inflammation that starts bone resorption. Ultra-processed diets are low in magnesium, potassium, and trace minerals needed for bone mineralisation. Phosphates used as preservatives can disrupt the calcium–phosphorus balance when consumed in excess, impairing proper mineral deposition.

Smoking, poor sleep, psychological stress, and ultra-processed diets elevate IL-6 and TNF-α signalling, shifting bone remodelling toward resorption. These cytokines suppress osteoblast activity and accelerate osteoclastogenesis.

Both sedentary behaviour and overtraining negatively affect bone, though through different mechanisms. Prolonged inactivity reduces mechanical loading, decreasing osteocyte signalling and increased bone resorption. This results in rapid bone loss, particularly in weight-bearing regions.

Overtraining, on the other hand, imposes excessive stress without sufficient recovery, elevating cortisol and suppressing anabolic hormones. When combined with inadequate energy intake, overtraining speeds up bone breakdown.

CHAPTER 13: AESTHETICS

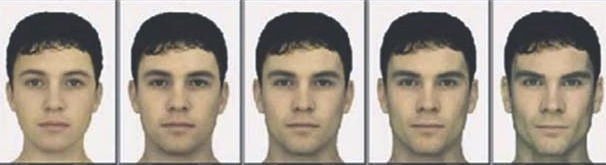

Skeletal aesthetics are closely tied to bone geometry, density, and alignment rather than bone mass alone. Facial structure, posture, and skeletal proportions influence perceived robustness and symmetry.

Craniofacial bones undergo continuous remodelling driven by mechanical stress, dental forces, and metabolic signalling. During childhood and teenhood, craniofacial growth is most pronounced, with bones of the jaw, midface, and cranial base responding to functions like proper breathing, chewing, and head posture.

Even after skeletal maturity, craniofacial bone is not frozen in place. Remodelling continues, although very slowly, letting subtle changes in bone density and contour in response to chronic loading patterns to appear. This affects mandibular robustness, zygomatic prominence, and facial bone quality, although it does not allow dramatic reshaping once growth plates have fused.

- Nose breathing promotes craniofacial development by encouraging proper tongue posture and maxillary expansion. When the tongue rests against the roof of the mouth (mewing), it exerts gentle pressure that guides the growth of the upper jaw and alveolar bone, supporting wider dental arches and a more defined midface. Mouth breathing leads to a narrow jaw, recessed cheekbones, and altered facial proportions, whereas habitual nasal breathing helps maintain balanced skeletal aesthetics and airway function.

- Chewing influences facial bone development through mechanical loading. The forces generated during mastication stimulate bone growth in the jaw and midface via mechanotransduction. Regular, varied chewing strengthens jaw bones and contributes to a wider, more defined midface, higher cheekbones, and improved facial symmetry.

- Molars: Heavy chewing on molars loads the posterior jaw, promoting alveolar bone thickness and mandibular robustness.

- Premolars: Chewing here helps maintain mid-arch width and supports proper occlusion.

- Incisors and canines: Front teeth engage less force but guide alveolar bone height and help shape the anterior maxilla, influencing chin projection and lip support.

- Head posture has an effect on facial bone development and aesthetics because the forces of gravity and muscle tension influence craniofacial growth. Forward (bad) head posture pulls the jaw backward, can flatten the midface, reduce chin projection, and compress the airway. Neutral/erect posture encourages optimal jaw alignment, proper tongue posture against the palate, and supports maxillary expansion. Maintaining correct posture strengthens neck and facial muscles, which indirectly load facial bones and stimulate bone remodeling. Consistently holding good head posture over time can enhance jawline definition, midface height, and overall facial symmetry, complementing benefits from chewing and nasal breathing, all of which you have no reason to not be doing.

Wide clavicles are ideal, but doing shoulder exercises can increase the width and attractiveness of your frame greatly if your clavicles are not as wide as you want, in addition to having good muscles everywhere else. Exercises I recommend are Reeves Deadlifts (Reeves shrugs), famously created by Steve Reeves in the 1900s, he claimed to have become 2 inches wider in his skeletal frame along with his muscles. Another is Hercules holds, wide-grip lateral pulldowns, and wide-grip deadhangs. In addition to these frame-based exercises, there is the regular shoulder press, lat raises, shrugs, etc.

Once you have gotten lean (although you will have to bulk to build muscle), you will obviously have to debloat to actually see your full facial bone structure. Eating too fast, overeating, laying down after a meal, being stressed, weird food combinations, chewing gum for too long, and an upset gut all bloat you. To debloat, you should stop eating high-inflammatory and high-sodium foods, eat collagenous foods (like bone broth), drink a lot of water, eat potassium-rich foods, eat natural diuretics (cucumber, celery, melon), and stop eating stuff like beans, cabbage, broccoli, spicy/fatty foods, sugar, and carbonated drinks.

I don't want to get too off-topic here, but it is very important to remember that great bones will not look great if you have these in addition: your skin is horrible, your hair is pish, and/or your physique is appealing, and many more. So always do this alongside skincare, haircare, going to the gym, and any other activity you are doing to look better. Collagen, as stated before will definitely help with your skin too.

CHAPTER 14: A PRACTICAL FRAMEWORK

Natural bone optimisation is most effective when training, nutrition, sleep, and sunlight are integrated into a consistent routine. Bone responds to repeated, appropriately timed stimuli rather than short bursts of extreme behaviour. Here is an example that I follow:

- Morning 6-8 AM-12 PM

- 20-40 mins outdoors within the first hours of waking, ideally without sunglasses or major protection (apart from sunscreen). This supports circadian alignment and vitamin D synthesis (depending on latitude and season) when UV levels will allow. Ideally you could watch the sun rise like I do.

- Breakfast: Protein sources (Eggs, Greek yogurt, or cheese), Carbohydrate (Oats, fruit, or wholegrain bread), Fat source (Dairy fat, egg yolks, or nuts). This combination supports insulin and IGF-1 signalling while supplying calcium, protein, and fat-soluble vitamins.

- Midday 12 PM

- Some light walking or activity to maintain mechanical signalling and circulation.

- Lunch: Protein (Meat, fish, or dairy), Carbohydrate (Rice, potatoes, or wholegrains), Micronutrients (Vegetables or fruit). Adequate energy intake here prevents cortisol elevation and supports training later in the day.

- Afternoon - early evening 1 PM-5 PM

- Training - 3-4 times a week. Here you need to focus on resistance and impact loading:

- Squats or leg press for axial compression

- Deadlifts or hip hinges

- Overhead presses or loaded carries

- Pull-ups or rows

- Optional low-volume impact work such as jumps or bounding

- Loads should be challenging but technically controlled, with an increase over time.

- A post-training meal should be protein-rich with carbohydrates to support recovery and anabolic signalling. Dairy-based options are very effective due to calcium and leucine content. I personally have Greek yogurt with berries or regular yogurt with berries and whole milk.

- Training - 3-4 times a week. Here you need to focus on resistance and impact loading:

- Evening 6 PM

- Dinner: Protein (Meat, fish, or dairy), Carbohydrate (Root vegetables or grains), Fats (Whole-food sources). This final meal supports overnight recovery and reduces late-night cortisol.

- Sleep duration should be a full 8-9 hours every night, with consistent sleep times, 10-11 PM until 6-8 AM. A low light exposure environment in the evenings, 1-2 hours before sleep, supports melatonin and GH release.

CHAPTER 15: ETHICAL AND SAFETY CONSIDERATIONS

Pharmacological enhancement

Injectable GH increases circulating IGF-1, but supraphysiological exposure does not selectively target bone. Instead, it promotes disproportionate soft tissue growth, fluid retention, insulin resistance, and organ enlargement. Bone changes, when they occur, often don;t adjust adequately, involving abnormal periosteal growth instead of structurally sound remodelling. Long-term use increases the risk of cardiomegaly, glucose intolerance, acromegaly in large doses, and potentially malignancy due to chronic mitogenic signalling.

IGF-1 injections pose even greater risk. IGF-1 is a potent growth signal with direct effects on cell proliferation. Elevating IGF-1 beyond physiological ranges increases the risk of uncontrolled tissue growth and disrupts normal growth hormone regulation. In bone, this can lead to imbalanced remodelling rather than coordinated strengthening. Excessive IGF-1 signalling is associated with increased cancer risk, hypoglycaemia, and long-term endocrine instability.

Romosozumab is a monoclonal antibody that increases bone formation while simultaneously suppressing bone resorption by inhibiting sclerostin, making it very effective for treating severe osteoporosis and reducing fracture risk in patients. In non-osteoporotic individuals, it can increase bone mineral density (BMD), but these gains do not mirror physiological optimisation and may disrupt normal bone remodelling balance. It also carries massive downsides, including a risk of heart attacks, strokes, and death from cardiovascular disease.

MK-677 is a ghrelin receptor agonist that increases endogenous GH and IGF-1 secretion without injections. Although often marketed as “safer,” it chronically elevates anabolic signalling independent of mechanical loading or circadian regulation. Reported risks include insulin resistance, increased appetite leading to fat gain, water retention, and impaired glucose tolerance. Bone effects are indirect and do not mimic natural developmental accrual.

Oxandrolone (Anavar) increases BMD by activating androgen receptors on osteoblasts and suppressing resorption. In healthy individuals, it accelerates bone turnover rather than inducing true structural adaptation. Risks include suppression of endogenous testosterone, dyslipidaemia, hepatic strain, and long-term endocrine disruption. Bone changes regress after cessation if mechanical and nutritional signals are not maintained.

Testosterone supports cortical bone thickness partly through aromatisation to oestrogen, which suppresses osteoclast activity. Exogenous administration overrides hypothalamic–pituitary regulation, often resulting in long-term hormonal suppression. Cardiovascular risk, erythrocytosis, lipid disturbances, infertility, and dependency are well documented. Bone benefits do not justify systemic risk in non-deficient individuals.

Nandrolone (Deca-Durabolin) has been studied for osteoporosis due to its anabolic effects on bone and muscle. However, its strong suppression of endogenous gonadal function, adverse cardiovascular effects, and neuroendocrine disruption outweigh any skeletal benefit outside disease contexts.

The SARM (Selective Androgen Receptor Modulator) Ostarine (MK-2866) activates androgen receptors with partial tissue selectivity and has shown modest bone-protective effects in animal models. Human data remains limited, and endocrine suppression has been seen even at low doses. Long-term safety is unknown.

Ligandrol LGD-4033), another SARM, increases lean mass and may indirectly stimulate bone through increased mechanical loading. However, it causes significant suppression of endogenous testosterone and alters lipid profiles. Bone effects are secondary and reversible, while endocrine risks persist.

Risks of nutrient excess

Excessive nutrient intake does not equate to superior bone health. Overconsumption of calcium can impair absorption of other minerals and increase the risk of soft tissue calcification when vitamin K and magnesium are insufficient. Excessive vitamin D intake can disrupt calcium homeostasis and cause toxicity. High-dose supplementation without deficiency or medical indication introduces imbalance rather than optimisation.

CHAPTER 16: EMERGING AND EXPERIMENTAL THERAPIES IN BONE

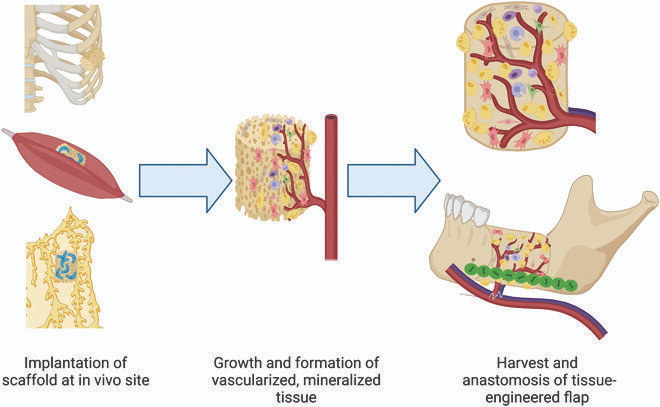

While lifestyle, nutrition, and mechanical loading remain the best determinants of bone mass across the lifespan, modern research has developed a range of experimental strategies aimed at directly inducing bone formation or repairing skeletal deficits.

- Mesenchymal Stem Cell–Based Bone Engineering: Mesenchymal stem cells derived from bone marrow, adipose tissue, or dental pulp can be seeded onto osteoconductive scaffolds such as β-tricalcium phosphate (biodegradable material used as a scaffold for bone regeneration) or bioactive glass. When exposed to osteogenic media, these cells differentiate into osteoblast-like cells and deposit mineralised matrix. Animal studies demonstrate increased bone volume and mechanical strength in critical-size defects, though issues of cell survival, integration, and scalability remain unresolved in humans.

- BMP-Based Controlled Delivery Systems: Bone morphogenetic proteins, particularly BMP-2, are potent osteoinductive molecules delivered via hydrogels or nanocarriers. Controlled-release systems aim to localise BMP activity and reduce adverse effects such as ectopic ossification. Despite strong bone-forming capacity, safety concerns and cost limit widespread use currently.

- 3D-Printed and AI-Optimised Bone Constructs: Advanced manufacturing techniques allow the creation of patient-specific scaffolds with optimised porosity, stiffness, and growth factor distribution.

- Wnt Signalling Modulation: The Wnt/β-catenin pathway is a central regulator of bone formation. Experimental modulation has shown dramatic increases in bone mass, but this pathway is also implicated in cancer development, making manipulation unsafe.

CONCLUSION

Bone mass and strength are shaped by mechanical, nutritional, hormonal, and environmental factors across your life. Mechanical loading, nutritional quality, hormonal balance, sleep quality, gut health, and sunlight exposure all contribute to bone growth, and missing even one can slow you down, or even damage bone development.

You should be training 3-4 times a week, sleep 9 hours from 11 PM to 6/8 AM everyday, with outside sun exposure in the mornings preferred. Your diet should consist of: High quality protein spread throughout the day, carbohydrates, dietary fat, calcium, phosphorus, vitamin D, vitamin K2, magnesium, zinc, boron, copper, manganese, silicon, dietary nitrates (beetroot juice, pomegranates, etc), vitamin C, and amino acids.

Extreme approaches, like pharmacological enhancement or excessive loading, introduce unnecessary risk and do not override what you can achieve naturally. Meaningful and healthy bone development requires consistency and patience.

Hope you enjoyed and learnt something from this