til<3D

Iron

- Joined

- Jan 12, 2026

- Posts

- 8

- Reputation

- 1

This is a comprehensive guide for both beginners and advanced lifters. Everything you'll read here is based on my personal experience as a science-based lifter.

If the term "science-based lifting" already turns you off, feel free to leave now — because this guide is 100% science-based and 100% evidence-driven. No guesswork, no bro-science, no "this worked for me once so it must be universal."

Before we start, I want to make one thing clear: this is very likely the most extensive true guide you'll find on this forum. The goal is not to overwhelm, but to explain things properly — from the ground up — and connect the dots most people never explain.

I'm writing this guide in collaboration with ChatGPT. That's why you won't hear any insults here - unfortunately. My input is written in my native language, and ChatGPT helps translate and structure everything into clear English. The reason is simple:

Let's get started.

Training determines whether you build muscle — or whether nothing happens at all.

You can have perfect nutrition.

You can sleep eight hours every night.

You can take every supplement on the market.

If your training is bad, you will not build muscle.

Nutrition, sleep, and supplements do not build muscle by themselves. They only support the adaptation that is created by training.

Mechanical tension is the stimulus that tells your body: "We need to adapt. We need more muscle."

Things that do NOT directly build muscle:

If mechanical tension is not present — meaning sufficiently heavy load, controlled execution, and proximity to failure — hypertrophy will be minimal or nonexistent.

These are the reps where mechanical tension is highest.

That is why, in every program presented in this guide, we will work with:

Low effort does not build muscle. Hard sets do.

It is the only reliable short-term indicator that you are actually building muscle.

If, under the same conditions:

You have built muscle.

Progressive overload is different.

It is the only short-term feedback system that tells you your training is working.

If performance goes up under standardized conditions, muscle tissue had to adapt. There is no workaround, no placebo, no "mind-muscle connection" explanation that replaces this.

You must keep a training log.

For every exercise, you write down:

No logbook = no data.

No data = no progress.

How it should look like:

Pull-FB:

Exercise - last Load and reps from first set of last week

Weight x Reps (+ note if necessary)

Weight x Reps (+ note if necessary)

Exercise - last Load and reps from first set of last week

Weight x Reps (+ note if necessary)

Weight x Reps (+ note if necessary)

…

Short term, progressive overload is the signal.

That's why everything in this guide — split selection, volume, exercise choice — ultimately serves one purpose: making progressive overload possible and repeatable.

We already know we work in the 5–8 rep range at 0–1 RIR. But how do we actually progress from session to session?

The answer is double progression.

Hitting a muscle at least twice per week is considered optimal.

The reason is simple: A muscle only grows for roughly 24–48 hours after a sufficient training stimulus. After that window, muscle protein synthesis returns to baseline. If you wait too long before training that muscle again, you are wasting potential growth time.

That is why, throughout this guide, we will generally work with higher frequencies rather than once-per-week "bro splits."

Other highly effective splits include:

In this guide, we will use a more practical and recovery-oriented approach:

Volume will be planned based on sleeps, not weeks.

The key question is not: "How many sets per week do I do?"

The key question is: "How many sleeps do I have to recover before I train that muscle again?"

Examples:

General guidelines:

More volume than this does not automatically mean more growth — it often just means more fatigue and worse performance in the next session.

Planning volume around sleeps:

This is not true.

No split inherently prioritizes anything. A Push/Pull/Legs split does not prioritize chest. An Upper/Lower split does not prioritize back. A Full Body split does not prioritize legs.

The split does not determine priority. Exercise order does.

Train it first.

When you are fresh — not pre-fatigued, not systemically tired — you will:

Instead of this order:

That is prioritization.

That said, if you really don't want to train legs properly, there are still workable (though suboptimal) options, such as:

Avoiding leg training is a choice, not an optimal strategy.

You see it all the time:

This is wasting time and recovery capacity.

If you do:

Now, if you also add:

This is redundant.

Both exercises train the same muscle action. The second one does not add anything meaningful. It just costs you time and recovery capacity.

Biceps:

Instead of wasting that time and recovery on redundant work, you could:

We do both Chest Press and Butterfly for chest.

We do both Squats (or Hack Squat) and Leg Extensions for quads.

Wait — didn't we just say redundancy is bad?

This is NOT redundancy. Here's why:

Isolation exercises — where only one joint moves, and the target muscle works alone

Compound exercises — where multiple joints move, and multiple muscles work together

One isolation exercise (to fully isolate the target muscle)

+

One compound exercise (to load the movement pattern more heavily)

This ensures:

But doing multiple isolations or multiple compounds for the same muscle action? That's still wasted time and recovery.

But here's what most people don't understand:

To maximize mechanical tension, you need optimal execution.

To develop optimal execution, you need neurological adaptation.

Neurological adaptation takes time — and consistency.

Every time you switch exercises, your body has to:

Your muscles respond to mechanical tension.

If you want to maximize tension, you need to maximize performance — and that requires neurological efficiency, which only comes from repetition.

Changing exercises every week is not "keeping the muscle guessing."

It's keeping your nervous system guessing — and that limits your progress.

Let's walk through a practical example using a Full-Body Push / Full-Body Pull setup.

Full-Body Push Day – Involved Muscle Groups

On a push-focused full-body day, we train:

Shoulders

Triceps

Quads

We use both:

Glutes

Adductors

Full-Body Pull Day – Involved Muscle Groups

On a pull-focused full-body day, we train:

We use:

Upper Back / Traps

Rear Delts

Biceps

Hamstrings

Abs

Complete Full-Body Push / Full-Body Pull Training Program

This is a 4-day training split that alternates between two Push and two Pull variations:

Weekly Schedule:

Program Notes:

They can directly improve your performance on your working sets.

Many people experience this: They perform more reps on their second working set than on their first.

Why? Because their warm-up was inadequate.

PAP is a short-term increase in muscle performance that occurs when your nervous system and muscles are primed for maximum effort.

In simple terms: Your body becomes "ready" to produce maximum force.

Your warm-up progression might look like this:

Done correctly, they directly improve your working-set performance.

Use PAP, and make sure your first working set is your best working set.

This is not negotiable.

If your form changes, your progressive overload data becomes meaningless. You're not comparing apples to apples anymore.

Use a phone on a tripod and record each working set from the same angle every session. Compare your execution to the previous week.

If the form is the same and the load or reps increased → you progressed.

If the form deteriorated → the progression doesn't count.

Standardization is everything.

Lift explosively. Move the weight with maximum intent.

Eccentric (lowering phase): Controlled, but not exaggerated.

Lower the weight at a speed where, if someone yelled "STOP!", you could actually stop the movement.

This means:

ROM matters for standardization.

You need to use the same range of motion every session so that your progressive overload is valid.

You don't necessarily need to pull all the way down until your upper arm touches your torso — but if that's the ROM you use, then you must use that same ROM every session.

Pick a ROM that:

The rule is simple: Rest until your heart rate returns to baseline.

After a hard set of squats at 0 RIR, you will need significant rest — potentially 3–5 minutes or more — because the systemic demand is high.

After a set of preacher curls, you might only need 1–2 minutes, because the systemic fatigue is much lower.

The key: Don't rush. Wait until your breathing has normalized and your heart rate is back to resting levels.

Instead:

There are no exceptions.

This is not "sometimes" or "on certain exercises." This is the standard for every working set in this system.

If you're not training close to failure, you're not creating sufficient mechanical tension — and that means suboptimal growth.

Hard sets build muscle. Easy sets do not.

You are not tougher, stronger, or "more hardcore" because you refuse to use lifting straps.

You are just limiting your back development for no good reason.

Why?

Because your grip will fail long before your back is fully stimulated.

When you're doing heavy rows, pulldowns, or deadlifts without straps:

First: Even when using straps, you are still training your grip.

You still have to hold the bar. The straps just prevent your grip from being the limiting factor.

Second: If you actually want to train grip strength, then train it directly.

Don't handicap your back training just to get suboptimal grip work.

Add dedicated grip training:

It's smart training.

The goal of back training is to build your back — not to test your forearms.

If your grip fails at rep 5, but your lats could have done 8 reps, you just wasted a set.

Straps allow you to:

If you progress on the first set with identical execution, the second and third sets will also progress naturally over time.

You don't need to track progression separately for every set. Focus on the first set, and the rest will follow.

Large compound movements (Squats, Leg Press, etc.):

Increase by 5–10 kg when you hit 8 reps

Upper-body compounds (Chest Press, Rows, etc.):

Increase by 2.5–5 kg

Isolation movements (Curls, Lateral Raises, etc.):

Increase by 1–2.5 kg

The heavier the exercise and the more muscle mass involved, the larger the jumps can be.

Why?

Because you are already adjusting volume based on recovery windows. You're not accumulating excessive fatigue in the first place.

Most people need deloads because they program too much volume and don't respect recovery. If you avoid that mistake, planned deloads become redundant.

There are two main reasons to do cardiovascular training:

This is not optional if you care about long-term health.

If your conditioning is poor, you will experience cardiovascular failure before muscular failure.

This means:

You can structure this however it fits your schedule:

In a Cut: You can increase as needed — there is no upper limit

Do NOT do cardio immediately before your resistance training.

If you do cardio right before lifting, you will:

The concern: Cardio creates systemic fatigue, which could theoretically interfere with muscle growth.

The reality: Cardio and resistance training use different muscle fiber types:

In fact, improved cardiovascular capacity supports better training performance — which ultimately supports better gains.

Why?

Because we train in the 5–8 rep range at 0–1 RIR, lactate does not accumulate in the muscle during the set.

This means:

This can help you confirm that your setup and execution are correct. But this is diagnostic, not your regular training approach.

One potential difference:

Advanced lifters may benefit from including slightly more isolation exercises in their programs.

However: Even beginners should use plenty of isolation exercises.

Why?

Isolation exercises allow you to recruit more motor units specifically for the target muscle, without interference from synergists or stabilizers.

This makes them highly effective for hypertrophy — regardless of training experience.

If the term "science-based lifting" already turns you off, feel free to leave now — because this guide is 100% science-based and 100% evidence-driven. No guesswork, no bro-science, no "this worked for me once so it must be universal."

Before we start, I want to make one thing clear: this is very likely the most extensive true guide you'll find on this forum. The goal is not to overwhelm, but to explain things properly — from the ground up — and connect the dots most people never explain.

I'm writing this guide in collaboration with ChatGPT. That's why you won't hear any insults here - unfortunately. My input is written in my native language, and ChatGPT helps translate and structure everything into clear English. The reason is simple:

- I don't feel like writing everything out in German and translating it afterward, and

- writing has never been my strongest skill — clarity and correctness matter more than fancy wording.

Let's get started.

PART 1: TRAINING FUNDAMENTALS

Training – The Foundation of Everything

Training is by far the most important factor when it comes to building muscle. It's not even close.Training determines whether you build muscle — or whether nothing happens at all.

You can have perfect nutrition.

You can sleep eight hours every night.

You can take every supplement on the market.

If your training is bad, you will not build muscle.

Nutrition, sleep, and supplements do not build muscle by themselves. They only support the adaptation that is created by training.

Muscle Growth: What Actually Builds Muscle

When it comes to hypertrophy, there is one primary driver: mechanical tension.Mechanical tension is the stimulus that tells your body: "We need to adapt. We need more muscle."

Things that do NOT directly build muscle:

- metabolic stress

- the pump

- sweating

- soreness

- feeling exhausted after a workout

If mechanical tension is not present — meaning sufficiently heavy load, controlled execution, and proximity to failure — hypertrophy will be minimal or nonexistent.

Repetitions, Intensity, and Proximity to Failure

We know from both research and practical experience that the last ~5 repetitions of a set create the majority of the hypertrophy stimulus.These are the reps where mechanical tension is highest.

That is why, in every program presented in this guide, we will work with:

- 5–8 repetitions per set

- 0–1 RIR (Reps in Reserve)

Low effort does not build muscle. Hard sets do.

Progressive Overload – What It Actually Is

Progressive overload is not optional.It is the only reliable short-term indicator that you are actually building muscle.

If, under the same conditions:

- same exercise

- same technique

- same range of motion

- same setup

- same nutrition

- same training time

You have built muscle.

Why Progressive Overload Matters

Muscle growth is not something you can feel from session to session. Visual changes take time, and soreness means nothing.Progressive overload is different.

It is the only short-term feedback system that tells you your training is working.

If performance goes up under standardized conditions, muscle tissue had to adapt. There is no workaround, no placebo, no "mind-muscle connection" explanation that replaces this.

What Progressive Overload Is NOT

- It is not chasing a pump

- It is not random PRs with worse form

- It is not ego lifting

- It is not adding volume without progression

The Importance of a Training Log

Because of this, we track everything.You must keep a training log.

For every exercise, you write down:

- the machine or variation used

- the load

- the repetitions performed

No logbook = no data.

No data = no progress.

How it should look like:

Pull-FB:

Exercise - last Load and reps from first set of last week

Weight x Reps (+ note if necessary)

Weight x Reps (+ note if necessary)

Exercise - last Load and reps from first set of last week

Weight x Reps (+ note if necessary)

Weight x Reps (+ note if necessary)

…

Short-Term vs. Long-Term Indicators

Long term, you will see changes in your physique.Short term, progressive overload is the signal.

That's why everything in this guide — split selection, volume, exercise choice — ultimately serves one purpose: making progressive overload possible and repeatable.

Progressive Overload in Practice – The Double Progression Method

Now that we understand why progressive overload matters, we need to understand how to apply it systematically.We already know we work in the 5–8 rep range at 0–1 RIR. But how do we actually progress from session to session?

The answer is double progression.

How Double Progression Works

Here's the simple rule:- You start with a weight you can perform for 5 clean reps (at 0–1 RIR)

- Every session, you try to add reps with that same weight

- Once you reach 8 reps with that weight, you increase the load

- With the new, heavier weight, you drop back down to 5 reps — and repeat the cycle

Practical Example: Lat Pulldown

- Week 1: 80 kg × 5 reps

- Week 2: 80 kg × 6 reps

- Week 3: 80 kg × 7 reps

- Week 4: 80 kg × 8 reps → progression threshold reached

- Week 5: 85 kg × 5 reps → weight increased, reps reset

PART 2: PROGRAM DESIGN

Training Frequency and Split Selection

Based on the latest scientific evidence, we know that a higher training frequency is superior for hypertrophy.Hitting a muscle at least twice per week is considered optimal.

The reason is simple: A muscle only grows for roughly 24–48 hours after a sufficient training stimulus. After that window, muscle protein synthesis returns to baseline. If you wait too long before training that muscle again, you are wasting potential growth time.

That is why, throughout this guide, we will generally work with higher frequencies rather than once-per-week "bro splits."

Recommended Training Splits

The following splits are all solid, evidence-based options and work very well when programmed correctly:- Upper / Lower

- Push-FB / Pull-FB

- Full Body Every Other Day (FEOD)

- Push Pull Legs

Other highly effective splits include:

- Anterior / Posterior

- Torso / Limbs (Maybe too much for your arms)

- Full Body 3x per week

Training Volume per Muscle Group – A Sleep-Based Approach

When talking about training volume, most people think in weekly sets per muscle group.In this guide, we will use a more practical and recovery-oriented approach:

Volume will be planned based on sleeps, not weeks.

The key question is not: "How many sets per week do I do?"

The key question is: "How many sleeps do I have to recover before I train that muscle again?"

What Do We Mean by "Sleeps"?

A "sleep" simply refers to one full night of sleep between two sessions that train the same muscle group.Examples:

- Upper / Lower / Rest / Upper → 3 sleeps between upper-body sessions

- Full Body Every Other Day (FEOD) → 2 sleeps between full-body sessions

- Push / Pull / Legs → 4 sleeps before the same muscle group is trained again

Volume Allocation Based on Sleeps

Instead of distributing volume across a calendar week, we distribute volume across recovery windows.General guidelines:

- 2 sleeps → 1–3 sets per muscle group (3 sets maximum)

- 3 sleeps → 2–5 sets per muscle group (5 sets maximum)

- 4 sleeps → up to ~6 sets per muscle group

More volume than this does not automatically mean more growth — it often just means more fatigue and worse performance in the next session.

Why This Works

Muscle growth happens during recovery. The more recovery time you have, the more high-quality volume you can tolerate and benefit from.Planning volume around sleeps:

- respects individual recovery

- works across different splits

- prevents unnecessary junk volume

Muscle Prioritization – How to Actually Focus on a Muscle Group

There is a common misconception: People think that certain splits "prioritize" certain muscle groups.This is not true.

No split inherently prioritizes anything. A Push/Pull/Legs split does not prioritize chest. An Upper/Lower split does not prioritize back. A Full Body split does not prioritize legs.

The split does not determine priority. Exercise order does.

How to Prioritize a Muscle Group

If you want to prioritize a muscle group, the method is extremely simple:Train it first.

When you are fresh — not pre-fatigued, not systemically tired — you will:

- lift heavier weights

- perform more quality reps

- execute with better technique

- recover better between sets

Practical Example: Prioritizing Shoulders

Let's say you want to focus on shoulder development.Instead of this order:

- Chest Press

- Pec Deck

- Lateral Raises

- Triceps Pushdowns

- Lateral Raises ← trained first, when fresh

- Chest Press

- Pec Deck

- Triceps Pushdowns

Why This Works

Your performance capacity is highest at the start of a session. By the time you reach the last exercises, you are:- neurally fatigued

- systemically tired

- less focused

That is prioritization.

If You Hate Training Legs (Reality Check Included)

Ideally, you should train everything.That said, if you really don't want to train legs properly, there are still workable (though suboptimal) options, such as:

- Upper Every Other Day

- Push / Pull (with minimal or no leg training)

Avoiding leg training is a choice, not an optimal strategy.

PART 3: EXERCISE SELECTION

Exercise Selection – Avoiding Redundancy and Wasted Time

One of the biggest mistakes people make when designing training programs is exercise redundancy.You see it all the time:

- Three different curl variations in the same session

- Four different rowing movements for the upper back

- Multiple chest presses from slightly different angles

This is wasting time and recovery capacity.

How to Choose Exercises Properly

The method is simple:- Identify the primary action of the muscle you want to train

- Choose one exercise that performs that action

- Do not add more exercises that perform the exact same action

Practical Example: Chest Training

The primary action of the chest is horizontal adduction of the humerus (bringing the upper arm across the body).If you do:

- Pec Deck / Butterfly Machine

Now, if you also add:

- Dumbbell Bench Press

This is redundant.

Both exercises train the same muscle action. The second one does not add anything meaningful. It just costs you time and recovery capacity.

What Redundancy Looks Like

Here are common examples of redundant exercise pairings:Biceps:

- Preacher Curls + Alternating Dumbbell Curls

→ Both perform elbow flexion with supination — redundant

- Rope Pushdowns + Straight-Bar Pushdowns

→ Both perform elbow extension — redundant

- Butterfly + Dumbbell Bench Press

→ Both perform horizontal adduction — redundant

- T-Bar Row + Seated Cable Row + Chest-Supported Row

→ All perform horizontal pulling / scapular retraction — redundant

Why This Matters

Every exercise you do:- costs energy

- creates fatigue

- requires recovery

Instead of wasting that time and recovery on redundant work, you could:

- train another muscle group

- add more rest between sets for better performance

- leave the gym earlier and recover better

How to Check for Redundancy

Ask yourself two questions:- What is the primary muscle action of this exercise?

- Am I already doing another exercise with the exact same action?

The Right Way: One Exercise Per Muscle Action

For chest:- One exercise for horizontal adduction (Pec Deck, Chest Press, etc.)

→ Done. Move on.

- One exercise for elbow flexion (Preacher Curls, Cable Curls, etc.)

→ Done. Move on.

- One exercise for elbow extension (Pushdowns, Overhead Extensions, etc.)

→ Done. Move on.

- saves time

- saves recovery capacity

- keeps training focused and efficient

- allows you to train more muscle groups or rest more between quality sets

When Two Exercises for the Same Muscle ARE Justified

Now, you might notice something in the example programs:We do both Chest Press and Butterfly for chest.

We do both Squats (or Hack Squat) and Leg Extensions for quads.

Wait — didn't we just say redundancy is bad?

This is NOT redundancy. Here's why:

Isolation vs. Compound Movements

There is a critical difference between:Isolation exercises — where only one joint moves, and the target muscle works alone

Compound exercises — where multiple joints move, and multiple muscles work together

Example 1: Chest

Butterfly / Pec Deck → Pure isolation- Only the shoulder joint moves (horizontal adduction)

- The chest works almost completely alone

- Triceps are not involved

- Both shoulder AND elbow joints move

- Chest performs horizontal adduction

- Triceps perform elbow extension

- Both muscles work together

- The Butterfly ensures the chest is fully stimulated in isolation

- The Chest Press allows you to load the movement pattern more heavily with triceps assistance

Example 2: Quads

Leg Extensions → Pure isolation- Only the knee joint moves (knee extension)

- Quads work alone

- Both knee AND hip joints move

- Quads perform knee extension

- Glutes perform hip extension

- Both muscles work together

- Leg Extensions isolate the quads completely

- Squats allow heavier loading through a multi-joint pattern

The Rule: One Isolation + One Compound = Optimal Coverage

For most major muscle groups, the ideal setup is:One isolation exercise (to fully isolate the target muscle)

+

One compound exercise (to load the movement pattern more heavily)

This ensures:

- all muscle fibers are reached

- mechanical tension is maximized

- you're not leaving growth on the table

What IS Still Redundant

The following would still be redundant:- Pec Deck + Dumbbell Flyes → both are isolation for horizontal adduction

- Chest Press + Incline Press → both are compounds with the same joint actions

- Leg Extensions + Sissy Squats → both are knee extension isolations

- Preacher Curls + Cable Curls → both are elbow flexion isolations

Conclusion

Two exercises for the same muscle group are justified when:- One is an isolation movement

- One is a compound movement

But doing multiple isolations or multiple compounds for the same muscle action? That's still wasted time and recovery.

Exercise Consistency – Why You Should NOT Change Exercises Every Week

We already established that mechanical tension is the primary driver of hypertrophy.But here's what most people don't understand:

To maximize mechanical tension, you need optimal execution.

To develop optimal execution, you need neurological adaptation.

Neurological adaptation takes time — and consistency.

The Problem with Constantly Changing Exercises

Let's say you train biceps like this:- Week 1: Preacher Curls

- Week 2: Incline Dumbbell Curls

- Week 3: Cable Curls

- Week 4: Hammer Curls

Every time you switch exercises, your body has to:

- coordinate new motor units

- learn the range of motion

- stabilize in a new way

- figure out how to optimally recruit the target muscle

The Better Approach: Stick with Exercises for Entire Training Blocks

Now compare that to someone who does:- Week 1–20: Preacher Curls (entire mesocycle)

- becomes more efficient at the movement every session

- recruits the biceps more effectively over time

- progressively overloads the same exercise with better execution

- maximizes mechanical tension because technique is no longer a limiting factor

When Should You Change Exercises?

There are only a few valid reasons to switch an exercise:- You've "mixed out" the exercise — meaning you can no longer progress on it effectively

- The exercise causes pain or discomfort that doesn't resolve

- Equipment is no longer available

Why "Muscle Confusion" Is Nonsense

Your muscles don't get "confused."Your muscles respond to mechanical tension.

If you want to maximize tension, you need to maximize performance — and that requires neurological efficiency, which only comes from repetition.

Changing exercises every week is not "keeping the muscle guessing."

It's keeping your nervous system guessing — and that limits your progress.

How to Build the Perfect Training Plan

At this point, we already know the key variables:- multiple splits work very well (as listed earlier)

- recovery limits our maximum usable volume

- we work in a fixed rep range (5–8 reps at 0–1 RIR)

Let's walk through a practical example using a Full-Body Push / Full-Body Pull setup.

Step 1: Identify the Muscle Groups for Each Day

Before choosing exercises, we first define which muscle groups are trained on each day.Full-Body Push Day – Involved Muscle Groups

On a push-focused full-body day, we train:

- Chest

- Shoulders

- Triceps

- Quads

- Glutes

- Adductors

Step 2: Choose Appropriate Exercises Based on Availability and Stability

We now select exercises that:- are available in most gyms

- allow high mechanical tension

- are stable and easy to progressively overload

- Pec Deck / Butterfly

- Chest Press (machine)

Shoulders

- Lateral Raise Machine

- Cable lateral raises

- Dumbbell lateral raises

- Shoulder Press 90*

Triceps

- Cable Triceps Pushdowns

Quads

We use both:

- Quad isolation: Leg Extensions

- Quad compound: Belt Squat or Hack Squat

Glutes

- Hip Thrusts

Adductors

- Adductor Machine

Full-Body Pull Day – Involved Muscle Groups

On a pull-focused full-body day, we train:

- Latissimus

- Upper Back / Trapezius

- Rear Delts

- Biceps

- Hamstrings

- Calves

- Abs

Step 3: Exercise Selection for Pull Day

LatissimusWe use:

- Vertical pull: Lat Pulldown or Neutral-Grip Pulldown

- Sagittal-plane movement: Single-arm cable row or Cable pullover

Upper Back / Traps

- Upper-back rowing movement: T-Bar Row or Wide-grip machine row

Rear Delts

- Reverse Pec Deck

- Cable rear-delt flyes

Biceps

- Preacher Curls

Hamstrings

- Lying Leg Curl

- Standing Calf Raise Machine

Abs

- Ab Machine with spinal flexion

- it allows progressive overload

- it includes active spinal flexion

Why This Approach Works

We:- start with the split

- define muscle groups

- choose stable, overload-friendly exercises

- avoid unnecessary complexity

- avoid redundant exercises

- easy to recover from

- easy to progress

- highly repeatable

- fully aligned with a science-based approach

- Add three different chest press variations

- Include four different rowing movements

- Program multiple redundant curl variations

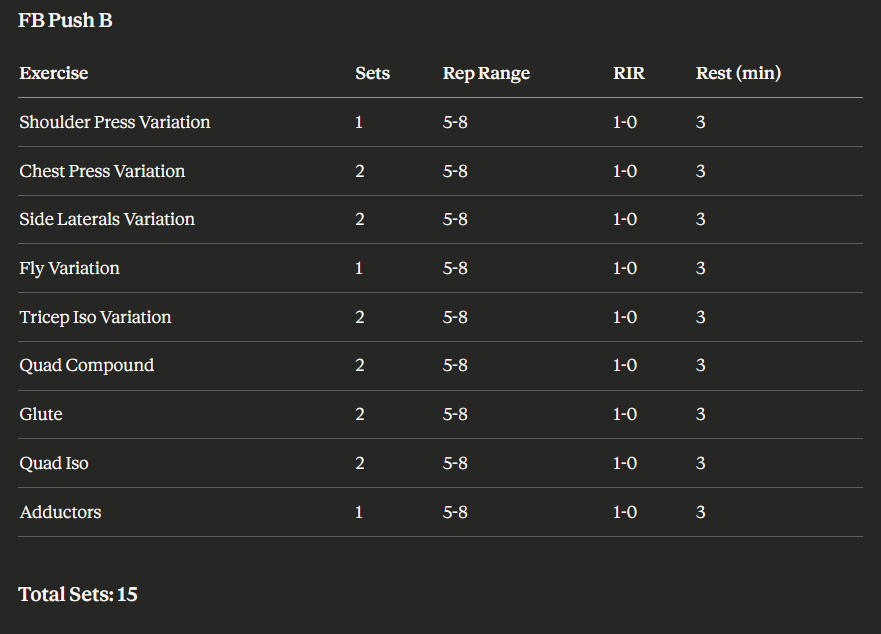

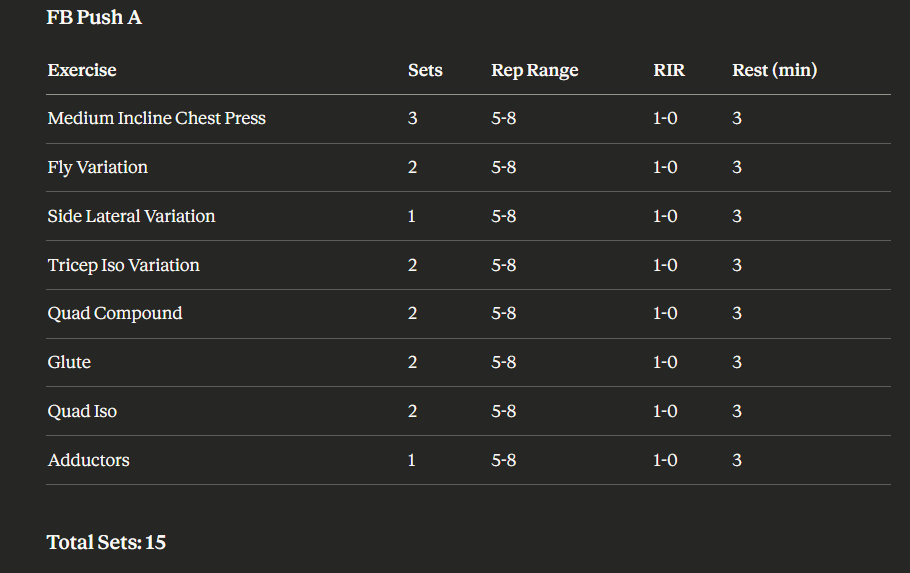

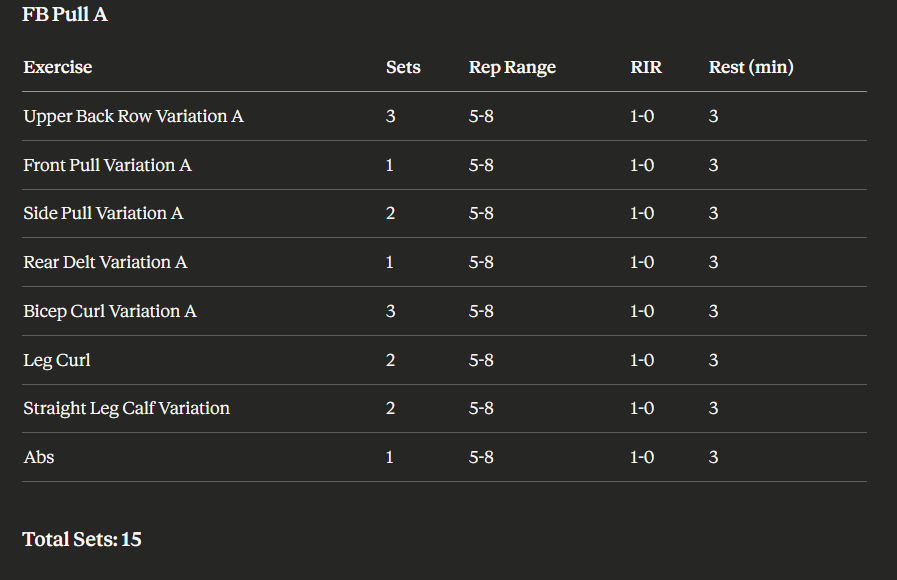

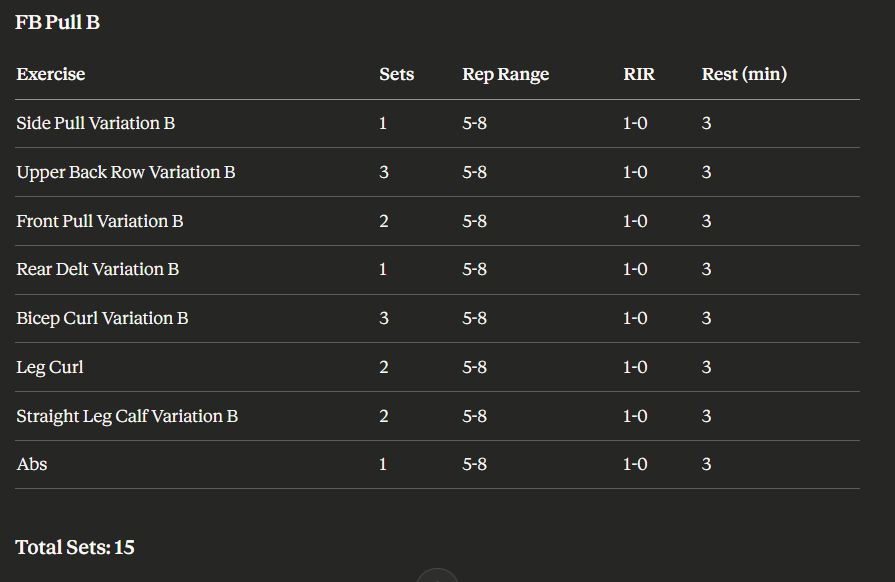

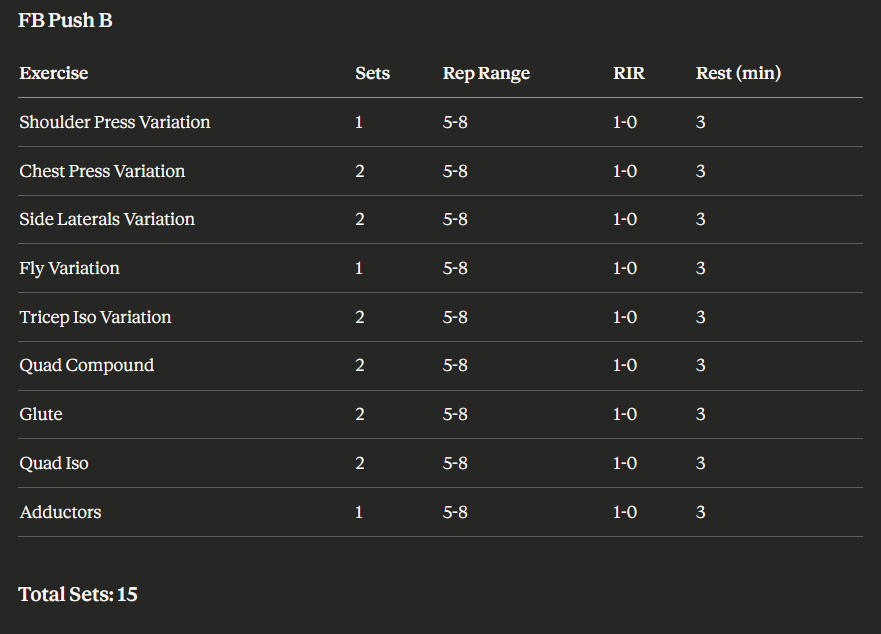

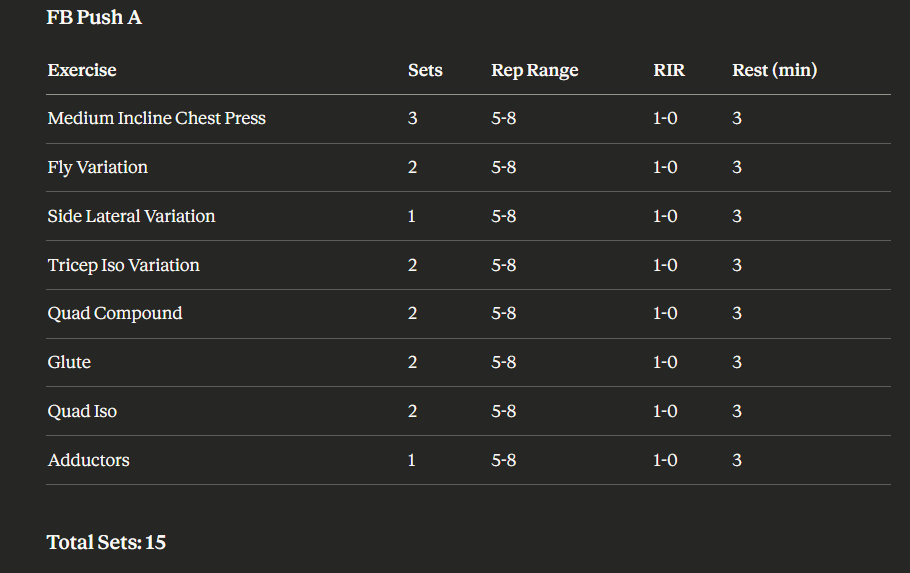

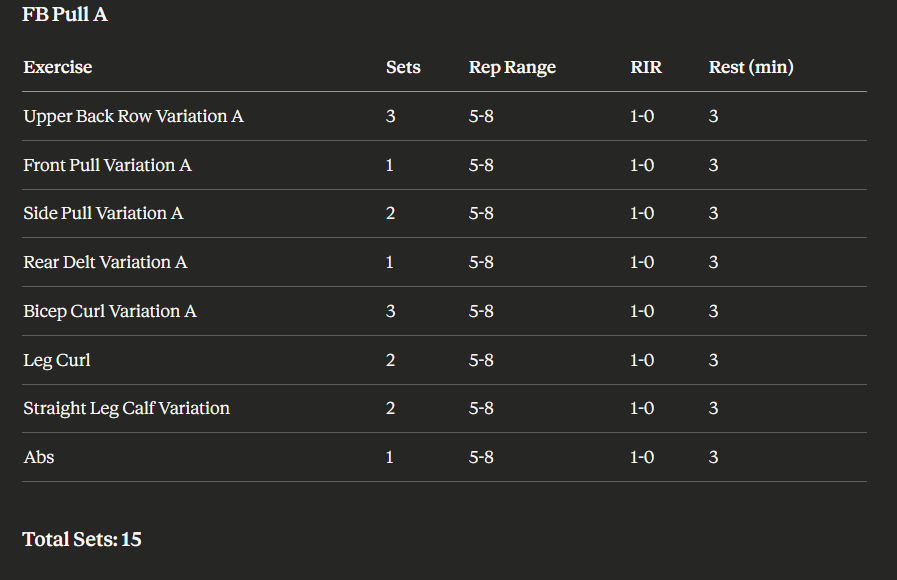

Complete Full-Body Push / Full-Body Pull Training Program

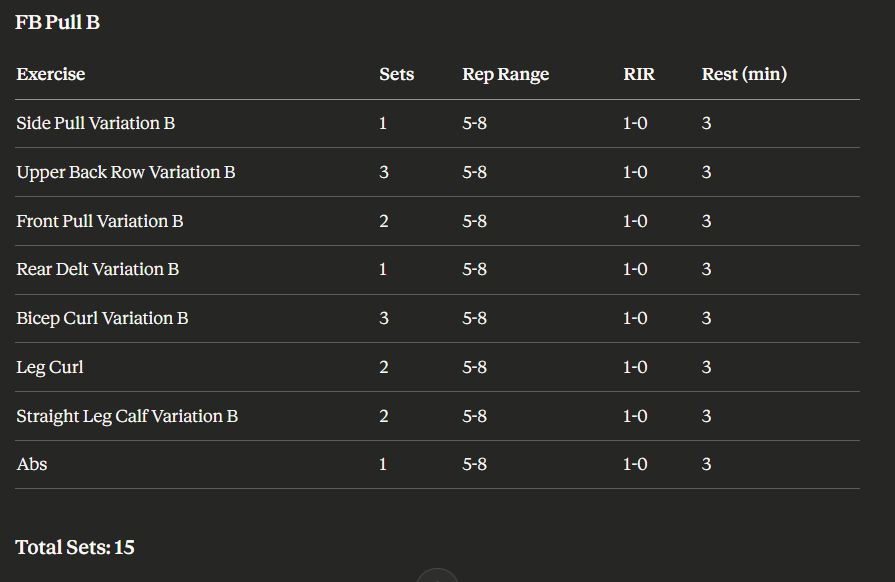

This is a 4-day training split that alternates between two Push and two Pull variations:

Weekly Schedule:

- Day 1: FB Push A

- Day 2: FB Pull A

- Day 3: Rest

- Day 4: FB Push B

- Day 5: FB Pull B

- Day 6: Rest

- Repeat

Program Notes:

- These are movement patterns, not specific exercises. Choose the actual exercises based on what equipment is available in your gym. For example, "Chest Press Variation" could be a machine chest press, barbell bench press, or dumbbell press — whatever you have access to and can progressively overload consistently.

- Each session totals exactly 15 working sets

- All sets are performed at 1-0 RIR (very close to or at failure)

- Rest periods are standardized at 3 minutes (adjust based on heart rate recovery)

- Exercise variations (A vs B) allow for continued neurological adaptation while preventing excessive CNS fatigue

- This structure provides 2 training sessions per muscle group per week with adequate recovery (2 sleeps between sessions)

- Once you select a specific exercise for each movement pattern, stick with it for the entire training block (12-20 weeks) to maximize progressive overload

- Beginner modification: If you are new to resistance training (less than 2-3 months of consistent training experience), start with 2-3 RIR instead of 1-0 RIR for the first 4-8 weeks. This allows you to learn proper exercise execution and minimize injury risk while your body adapts to hard training. Once your technique is solid and consistent, gradually progress to 1-0 RIR.

PART 4: EXECUTION & TECHNIQUE

Warm-Up Sets – More Than Just Injury Prevention

Warm-up sets are not just about avoiding injury.They can directly improve your performance on your working sets.

Many people experience this: They perform more reps on their second working set than on their first.

Why? Because their warm-up was inadequate.

How Many Warm-Up Sets?

The answer depends on three factors:- Is the muscle already warm? (e.g., if you already did another exercise for that muscle)

- Do you have any pain or discomfort? (you may need extra warm-up sets to prepare the joint)

- How heavy is your working weight? (heavier loads require more warm-up)

Post-Activation Potentiation (PAP) – Unlocking Peak Performance

To achieve maximum performance on your working sets, we want to trigger something called Post-Activation Potentiation (PAP).PAP is a short-term increase in muscle performance that occurs when your nervous system and muscles are primed for maximum effort.

In simple terms: Your body becomes "ready" to produce maximum force.

How to Achieve PAP

The method is straightforward:- Perform 1–2 reps at 85–95% of your working weight

- Rest for 30–60 seconds (until you feel ready)

- Perform your working set

Practical Example: Bench Press with 90 kg Working Weight

Let's say your working weight is 90 kg for 5–8 reps.Your warm-up progression might look like this:

- Warm-up Set 1: 50 kg × 7 reps

- Warm-up Set 2: 70 kg × 4 reps

- PAP Set: 90 kg × 1–2 reps

- Rest: 30–60 seconds (until you feel ready)

- Working Set 1: 90 kg × 5–8 reps (at 0–1 RIR)

Why This Works

The PAP set:- activates high-threshold motor units

- prepares your nervous system for maximum effort

- does not create significant fatigue (only 1–2 reps)

Key Takeaway

Warm-up sets are not filler work.Done correctly, they directly improve your working-set performance.

Use PAP, and make sure your first working set is your best working set.

Form & Technique – The Standardization Rule

Your technique must look identical to the week before.This is not negotiable.

If your form changes, your progressive overload data becomes meaningless. You're not comparing apples to apples anymore.

How to Ensure Consistency

The best method: film every set.Use a phone on a tripod and record each working set from the same angle every session. Compare your execution to the previous week.

If the form is the same and the load or reps increased → you progressed.

If the form deteriorated → the progression doesn't count.

Standardization is everything.

Tempo – How Fast Should You Lift?

Concentric (lifting phase): As fast as possible.Lift explosively. Move the weight with maximum intent.

Eccentric (lowering phase): Controlled, but not exaggerated.

Lower the weight at a speed where, if someone yelled "STOP!", you could actually stop the movement.

This means:

- Don't drop the weight uncontrolled

- But also don't take 5–10 seconds on the eccentric

Range of Motion (ROM) – Standardization Over Extremes

Full range of motion is important — but not for the reason most people think.ROM matters for standardization.

You need to use the same range of motion every session so that your progressive overload is valid.

Example: Lat Pulldown

Biomechanically, the latissimus has its best leverage at around 90 degrees of shoulder extension. You could, in theory, stop there and still get an excellent stimulus.You don't necessarily need to pull all the way down until your upper arm touches your torso — but if that's the ROM you use, then you must use that same ROM every session.

The point:

Extreme full ROM is not required for hypertrophy. What is required is consistent ROM so you can track progress accurately.Pick a ROM that:

- feels stable

- allows you to load the movement well

- can be repeated identically week after week

Rest Times Between Sets – Listen to Your Body

Rest times are not arbitrary numbers.The rule is simple: Rest until your heart rate returns to baseline.

After a hard set of squats at 0 RIR, you will need significant rest — potentially 3–5 minutes or more — because the systemic demand is high.

After a set of preacher curls, you might only need 1–2 minutes, because the systemic fatigue is much lower.

The key: Don't rush. Wait until your breathing has normalized and your heart rate is back to resting levels.

Unilateral Training (Single-Arm/Leg Work)

For single-arm or single-leg exercises, do not go directly from right to left.Instead:

- Perform the right side

- Rest until your heart rate normalizes

- Perform the left side

- Rest again before the next set

Training to Failure – Always 0–1 RIR

Yes. Every working set should be performed at 0–1 RIR.There are no exceptions.

This is not "sometimes" or "on certain exercises." This is the standard for every working set in this system.

If you're not training close to failure, you're not creating sufficient mechanical tension — and that means suboptimal growth.

Hard sets build muscle. Easy sets do not.

Lifting Straps – Stop Being Stupid About Them

Let's address something that needs to be said clearly:You are not tougher, stronger, or "more hardcore" because you refuse to use lifting straps.

You are just limiting your back development for no good reason.

The Simple Truth About Building a Big Back

If you want to build a thick, well-developed back, use lifting straps.Why?

Because your grip will fail long before your back is fully stimulated.

When you're doing heavy rows, pulldowns, or deadlifts without straps:

- Your forearms give out first

- Your back never reaches true mechanical failure

- You leave growth on the table

"But I Want to Train My Grip Strength!"

Two responses to this:First: Even when using straps, you are still training your grip.

You still have to hold the bar. The straps just prevent your grip from being the limiting factor.

Second: If you actually want to train grip strength, then train it directly.

Don't handicap your back training just to get suboptimal grip work.

Add dedicated grip training:

- Farmer's walks

- Dead hangs

- Grip trainers

The Reality

Using straps is not "cheating."It's smart training.

The goal of back training is to build your back — not to test your forearms.

If your grip fails at rep 5, but your lats could have done 8 reps, you just wasted a set.

Straps allow you to:

- push your back to true failure

- maximize mechanical tension on the target muscle

- progress more effectively

When to Use Straps

Use straps on:- Heavy rowing movements (T-Bar Rows, Cable Rows, etc.)

- Lat Pulldowns (especially with heavier loads)

- Deadlifts or RDLs (if grip is limiting)

- Exercises where grip isn't the issue (leg work, pressing, etc.)

PART 5: PROGRESSION & TROUBLESHOOTING

Double Progression – Does It Apply to All Sets?

Double progression applies primarily to the first set.If you progress on the first set with identical execution, the second and third sets will also progress naturally over time.

You don't need to track progression separately for every set. Focus on the first set, and the rest will follow.

Weight Jumps – Adjust Based on the Exercise

The size of weight increases depends on the exercise:Large compound movements (Squats, Leg Press, etc.):

Increase by 5–10 kg when you hit 8 reps

Upper-body compounds (Chest Press, Rows, etc.):

Increase by 2.5–5 kg

Isolation movements (Curls, Lateral Raises, etc.):

Increase by 1–2.5 kg

The heavier the exercise and the more muscle mass involved, the larger the jumps can be.

What to Do When You Stop Progressing

If you hit a plateau and can no longer add reps or weight, follow this checklist in order:- Check your execution

Is your form still identical to previous weeks? Film yourself and compare.

- Improve recovery

Are you sleeping enough? Managing stress?

- Improve nutrition

Are you eating enough? Getting adequate protein?

- Improve hydration

Are you drinking enough water throughout the day?

- Improve your warm-up

Are you using PAP effectively? Are you adequately prepared?

- Reduce grinding and "ego" reps

Are you pushing so hard that you're frying your CNS?

- Only then: Adjust volume

If everything else is dialed in and you still can't progress, try reducing volume for that muscle group by one set for 2 weeks and reassess.

Deload Phases – Not Necessary with Proper Volume Management

If you are managing volume intelligently using the sleep-based approach outlined earlier, deloads are generally unnecessary.Why?

Because you are already adjusting volume based on recovery windows. You're not accumulating excessive fatigue in the first place.

Most people need deloads because they program too much volume and don't respect recovery. If you avoid that mistake, planned deloads become redundant.

PART 6: ADDITIONAL CONSIDERATIONS

Cardio – Should You Do It?

Yes. Absolutely.There are two main reasons to do cardiovascular training:

Reason 1: Health and Longevity

Regular Zone 2 cardio training can increase your lifespan by approximately 17%.This is not optional if you care about long-term health.

Reason 2: Preventing Cardiovascular Failure During Training

When you perform exercises like squats or leg presses, you need adequate cardiovascular capacity.If your conditioning is poor, you will experience cardiovascular failure before muscular failure.

This means:

- Your legs could do more reps

- But your heart and lungs give out first

- You never reach true mechanical failure on the target muscle

How Much Cardio?

Minimum: 60 minutes per weekYou can structure this however it fits your schedule:

- 1 session of 60 minutes

- 6 sessions of 10 minutes (e.g., every morning)

- 2 sessions of 30 minutes

- Any combination that totals at least 60 minutes

In a Cut: You can increase as needed — there is no upper limit

When Should You Do Cardio?

Timing is generally flexible, with one exception:Do NOT do cardio immediately before your resistance training.

If you do cardio right before lifting, you will:

- be pre-fatigued

- perform worse on your working sets

- compromise your progressive overload

- On rest days (ideal)

- In the morning, with resistance training in the afternoon/evening

- After your resistance training (if you must do it on the same day)

Does Cardio Hurt Your Gains?

Short answer: Not really — and it may even help.The concern: Cardio creates systemic fatigue, which could theoretically interfere with muscle growth.

The reality: Cardio and resistance training use different muscle fiber types:

- Resistance training (5–8 reps at 0–1 RIR): Type 2 muscle fibers

- Zone 2 cardio: Type 1 muscle fibers

In fact, improved cardiovascular capacity supports better training performance — which ultimately supports better gains.

Mind-Muscle Connection – Does It Matter?

No. Mind-muscle connection is not important for hypertrophy in this system.Why?

Because we train in the 5–8 rep range at 0–1 RIR, lactate does not accumulate in the muscle during the set.

This means:

- You won't feel a "burn"

- You won't feel a strong pump

- You won't have a clear sensation that you're "hitting the muscle"

Optional Test:

If you're unsure whether you're targeting the right muscle, you can occasionally do a high-rep "feel" session (15–20 reps) to get feedback from the pump and burn.This can help you confirm that your setup and execution are correct. But this is diagnostic, not your regular training approach.

Beginners vs. Advanced Lifters – Is There a Difference?

Not really. The core principles remain the same.One potential difference:

Advanced lifters may benefit from including slightly more isolation exercises in their programs.

However: Even beginners should use plenty of isolation exercises.

Why?

Isolation exercises allow you to recruit more motor units specifically for the target muscle, without interference from synergists or stabilizers.

This makes them highly effective for hypertrophy — regardless of training experience.