ihatemySOST

Bronze

- Joined

- Sep 5, 2025

- Posts

- 479

- Reputation

- 770

Fire song

introduction :

Hello, I want to talk about an important topic today, which is the use of androgenic hormones to increase height, clavicle width, and the bone mass of the face and body. I personally believe this is a very important topic because the amount of false information circulating about it is huge, and people’s belief that it is a magic solution for improving appearance is somewhat concerning.

But the question is, do androgenic hormones really justify their negative effects? Do they really increase height, clavicle width, or facial bone mass, or is this simply placebo science? Well, I won’t answer these questions. Instead, I will present all the evidence that supports or refutes their effectiveness, and then you can draw your own conclusion.

be clear, this post will be divided into three sections: the first is the evidence that supports or refutes their effectiveness in increasing height, the second is for increasing clavicle width, and the third is for facial and body bone mass (size). Evidence will be presented from: 1. human studies, 2. animal studies, 3. genetically modified animal studies, and 4. in vitro studies on cells, either human or animal. It is also important to note that I will only use studies that used androgens that are non-aromatizable or have very low potential to convert into estrogen, to ensure that all effects, whether positive or negative, are due to androgens.

Now we will start with height. Due to the large number of studies on this topic, I will try to select the highest-quality ones. The first study is a cross-sectional study conducted on individuals with Turner syndrome. Twenty-nine participants received either Anavar or Fluoxymesterone, compared to 37 who received no treatment. When final height was measured, there was no significant difference; androgen treatment failed to increase final height, at least in this group [1].

In the second study, a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled design (a strong study design) was used. Children were divided into two groups: twenty children received 0.1 mg/kg Anavar, and twenty received a placebo. The results showed that growth rate improved, but there was no change in final height [2].

In the third study, conducted on 27 children aged from 3 to 17 years, Anavar doses ranged from 0.05 to 0.2 mg/kg. In fact, this study found that final height decreased for some individuals by 1.5–7.5 cm. Although predicted height, which is not always accurate, was used, the relatively large loss and the fact that bone age advanced rapidly make the reduction in expected final height plausible [3].

In the fourth study, 61 boys aged 9–19 with constitutional growth and puberty delay were treated with Fluoxymesterone at 0.05–0.24 mg/kg for 0.4–3.6 years and compared with 37 boys as a control group who received no treatment; final height did not increase compared to the control [4]. The fifth study included 36 prepubertal children with constitutional delay of growth and puberty, divided into 16 receiving a low dose of Anavar (0.12 mg/kg) and 11 receiving a high dose (0.22 mg/kg) with 21 controls; growth accelerated but bone maturation also accelerated, so there was no significant effect on final height [5]. In the sixth study, nine boys were treated with 0.1 mg/kg Anavar and seven were controls, and neither growth rate nor bone maturation changed, possibly because the dose was insufficient [6]. The seventh study, a double-blind, placebo-controlled trial, gave 30 pubertal children with idiopathic short stature 2.5 mg Anavar each and 30 received placebo; after two years, both groups had the same height, but bone age advanced five times faster in the Anavar group, likely reducing potential final height [7]. Study eight, using a low dose of Anavar on children with constitutional delay of puberty (12 treated and 12 controls), showed increased growth rate but also advanced bone maturation with no change in final height [9]. Study nine evaluated long-term Anavar treatment (30–57 months) with 18 boys receiving Anavar and 9 controls; growth rate increased but final height remained unchanged [10]. Study ten used Norethandrolone, a steroid with high anabolic and weak androgenic activity minimally convertible to estrogen, on 8 children; it did not enhance longitudinal growth but accelerated skeletal maturation [11]. Not all studies found no benefits, as some low-quality studies suggested small increases in predicted final height, but they lacked control groups and had weak designs [8]. Most high-quality studies show that androgenic treatment accelerates growth and bone maturation but does not increase final height. I could list more human studies, but they all reached the same conclusion. Anyone interested in more results can research online. Now, what about the effects of non-aromatizable androgenic/anabolic steroids on longitudinal growth in normal animals?

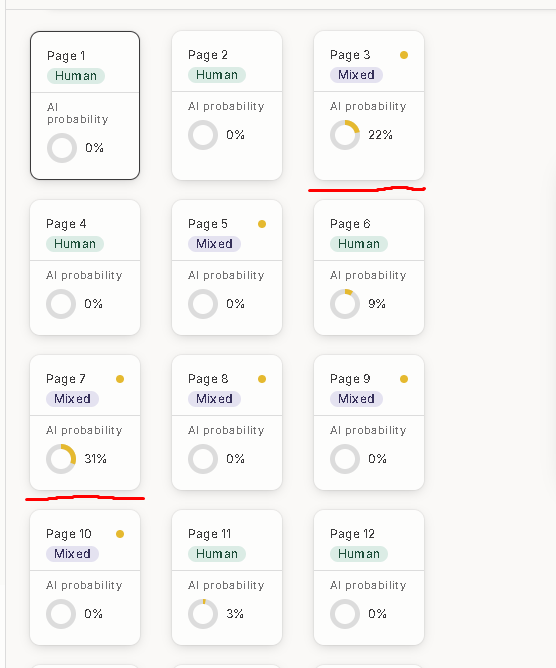

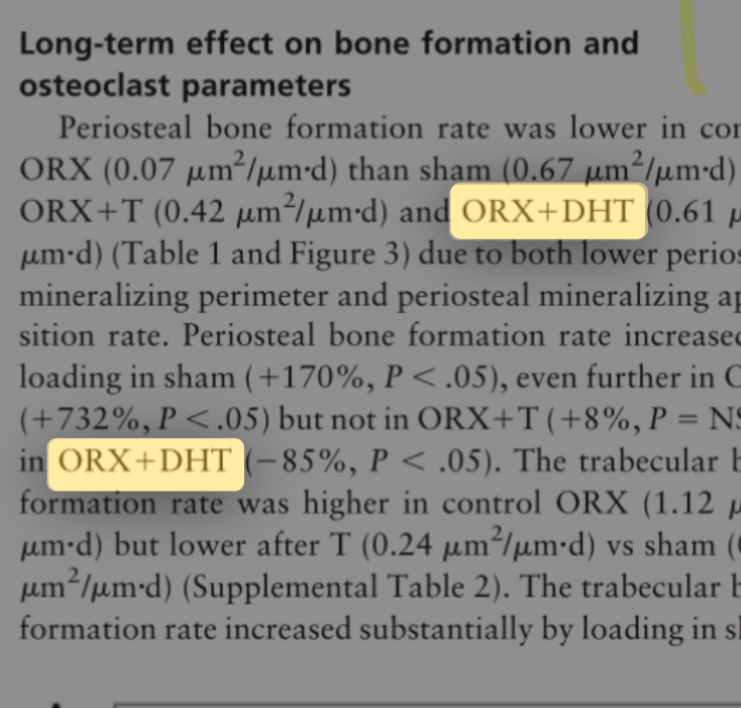

In the first study, scientists used Methenolone on prepubertal rats until near the end of puberty; it is a DHT-derived steroid, weakly androgenic, relatively strong anabolic, and non-aromatizable. The results were unusual: the steroid actually inhibited longitudinal femur growth in males but enhanced it in females [12]. In a second study using the same steroid with the same design, results were consistent with the first study: the compound significantly inhibited longitudinal bone growth, and by the end of the experiment, femur length in the treated group was notably shorter than in controls [13]. In a third study, Methenolone Enanthate was used again, producing similar results: humerus length was significantly reduced in males compared to controls, while females actually had longer bones [14]. Scientists also tested Nandrolone, a highly anabolic, weakly androgenic compound with minimal estrogen conversion. Like previous studies, it significantly inhibited longitudinal bone growth in males [15]. Another study found its effect neutral on femur length; the discrepancy may be due to differences in the age of the rats used [56]. Another study tested Trenbolone, a strongly androgenic and anabolic compound with a near-equal anabolic-to-androgenic ratio; as expected, it increased bone length in females, but in male rats, it slightly shortened bone length. The difference between treated and control males was minimal and not statistically significant [16]. Overall, the results in animals align closely with human findings: androgenic hormones in experimental animal studies either inhibit bone growth or have a mild effect. Androgens do not directly reduce longitudinal bone growth but can accelerate bone maturation, reducing the time available for vertical growth. Evidence in humans is limited and somewhat conflicting, likely due to differences in dose, target population, and individual response, whereas animal studies are more controlled and consistent. I previously mentioned genetically modified models with high AR expression in bone to increase sensitivity to androgens. Are there studies on this? Yes: scientists created mice overexpressing androgen receptors in mature and pre-mature bone cells. The result? Severe short stature in femur and overall body length. This is striking because the modification was only in bone cells, not cartilage. Interestingly, the modified mice had normal length for the first two months, then growth declined, strongly indicating that androgens accelerated bone maturation, limiting longitudinal growth (figure 1) [18].

(Figure 1: Femur length of genetically modified mice compared to normal mice, showing a clear shortening.)

So what about humans? Are there studies showing whether higher androgen sensitivity is linked to short stature, taller height, or normal height without significant effects? The answer is yes; several studies have looked into this. But first, an important point: studies measure the body’s androgen sensitivity through CAG repeat length. The longer the CAG repeat in the gene, the longer the PolyQ tract in the receptor, and the longer the PolyQ, the lower the receptor sensitivity. Conversely, shorter CAG repeats mean higher receptor sensitivity [17]. In the first study examining CAG length in lean and obese men, for lean men, increased CAG length (lower androgen sensitivity) had a positive effect on height, with r = 0.43 and p = 0.08, close to statistical significance but not quite, likely due to small sample size. For obese men, the relationship was stronger, r = 0.73 and p = 0.02, meaning lower androgen sensitivity was associated with greater height and unlikely to be by chance. When lean and obese men were combined, the relationship remained significant (p = 0.05): longer CAG = lower androgen sensitivity = taller height. Scientists explained this by noting that lower androgen sensitivity allowed growth plates to remain open longer [19]. This is not the only study: a second study on adult men also found that lower androgen sensitivity (longer CAG repeat) was associated with slightly increased height [20]. The difference isn’t huge, just a few centimeters, but it is real and statistically significant. Animal data strongly support this, and there is a clear biological rationale behind it.

Androgen effects on bone age advancement, whether AI can prevent negative effects, the pathways they activate in chondrocytes, local IGF-1 production, and lab effects can all be addressed. Androgens inhibit chondrocyte proliferation during the proliferative phase and slightly enhance it in the resting phase. In a study on chondrocytes from the growth plate of adolescent humans in the proliferative phase, testosterone and DHT together strongly inhibited proliferation in a dose-dependent manner [21]. Rat studies agree: testosterone inhibited proliferative chondrocytes with little or no effect on resting zone cells, while raising bone differentiation markers (ALP), indicating a shift toward ossification and growth plate closure. Negative effects appeared only in males, while effects in females were neutral or positive [22]. The negative effect was due to testosterone itself, not conversion to E2, as E2 had no effect on proliferative chondrocytes under the same conditions [23]. In another study on rat resting zone chondrocytes, low DHT concentrations slightly enhanced proliferation, but higher doses inhibited it and raised ALP levels [24]. Some studies found positive effects; in rat resting zone chondrocytes, DHT increased IGF-1 levels and promoted proliferation, but adding vitamin D with DHT eliminated proliferative effects and increased ossification markers such as ALP, with chondrocytes mineralizing in vitro [25]. Another study found that DHT and testosterone increased proliferation in proliferative zone chondrocytes, but testosterone inhibited proliferation in resting zone chondrocytes while DHT was neutral [26]. Overall, results are somewhat contradictory due to differences in chondrocyte origin, sample type, culture medium, and doses. In vitro studies show that effects are generally neutral, slightly positive, or negative.

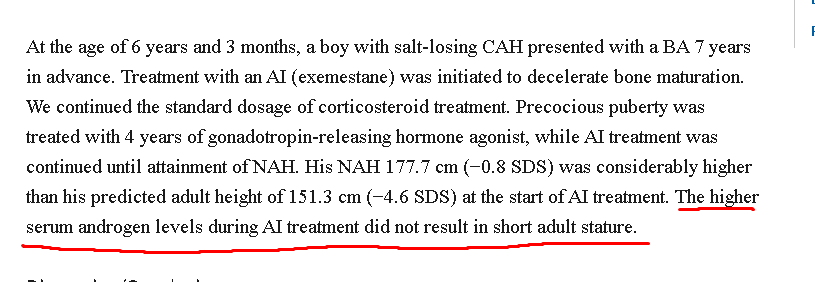

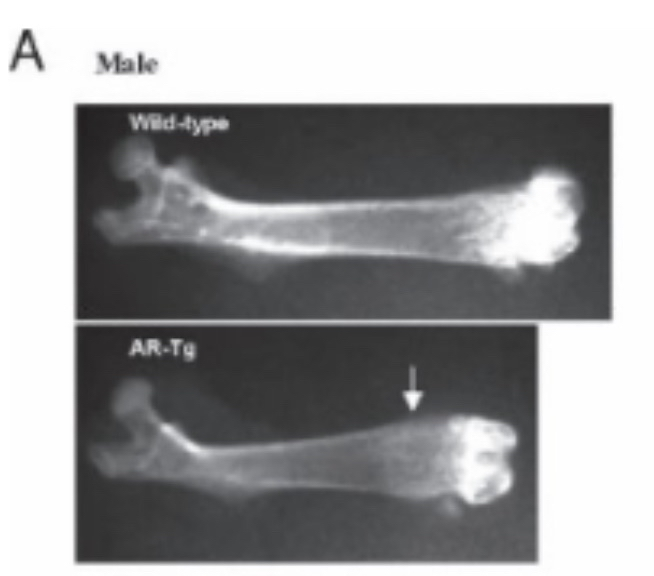

Now, regarding the most important question: can supraphysiological levels of androgens cause severe growth plate ossification, and can this effect be reversed by using an aromatase inhibitor? I will present the studies and let you draw your own conclusion. The first study, conducted on rats, directly addressed whether androgens induce bone maturation and whether a strong estrogen receptor antagonist could block this effect. Rats were divided into three groups: control, testosterone, and testosterone plus a strong estrogen receptor antagonist. Bone maturation was assessed radiographically and graded on four levels, with level four indicating complete cartilage fusion into bone. The results were striking. The group receiving testosterone plus the strong estrogen receptor antagonist showed bone maturation identical to the group receiving testosterone alone. Both groups achieved complete growth plate closure (level four), far more than the control group. At least in this rat study, androgens played a decisive role in bone maturation, and a strong estrogen receptor blockade did not prevent it [27][28]. Interestingly, the compound designed to fully block estrogen receptors was effective in preventing growth plate advancement caused by external estrogen injections, as bone age in the estrogen plus receptor antagonist group did not differ from controls [29].

(Figure 2: Image showing vertebral bone maturation; growth plates in the testosterone-treated groups reached level four, indicating complete closure)

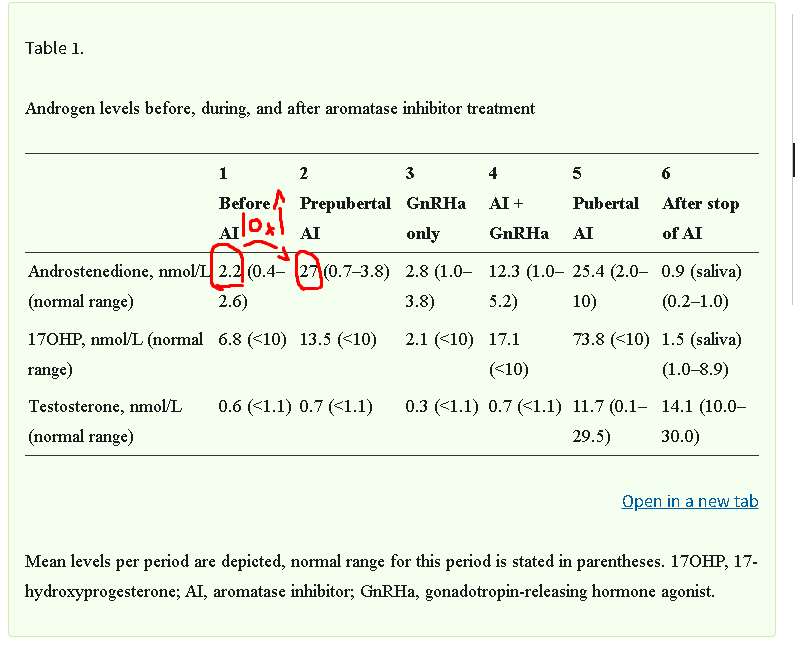

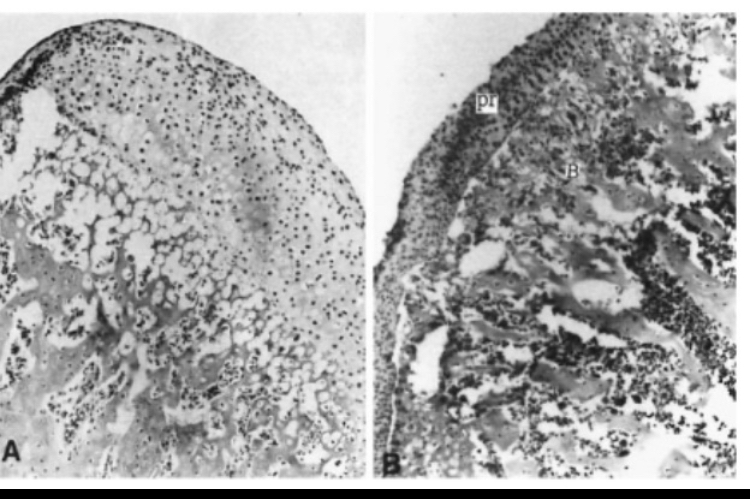

This is not the only study showing such results. In a second study, similar findings were observed, focusing on mandibular cartilage in rats. Scientists tested low, medium, and high testosterone concentrations and examined effects on cartilage growth and ossification. The results were surprising. At the medium dose, during the first third of the experiment, condylar cartilage volume doubled compared to controls, but after seven days, the cartilage underwent complete ossification. This did not occur with the high dose. The same medium dose that initially doubled cartilage growth caused all testosterone effects to manifest as accelerated ossification, ultimately leading to full closure, as shown in histological images. How do we know this ossification effect is due to direct androgen action and not local estrogen conversion? First, estrogen only accelerated ossification at very high doses, while medium-dose testosterone alone caused nearly complete growth plate ossification. Second, and more importantly, ossification was mediated by increased insulin-like growth factor 1 (IGF-1). Estrogen only increased IGF-1 production at very high doses, while testosterone strongly increased IGF-1 expression. Evidence shows that testosterone induces full growth plate ossification by upregulating IGF-1 gene expression in hypertrophic and prehypertrophic chondrocytes. Using an IGF-1 antibody completely blocked testosterone’s effect on ossification. Since estrogen did not increase IGF-1 expression while testosterone did, blocking IGF-1 abolished testosterone’s effect on ossification and chondrocyte differentiation. This provides direct and strong evidence that testosterone, not estrogen, is responsible for ossification in this model, although estrogen may still play a secondary role [49,30]

(Figure 3: Comparison of control group cartilage (a) with cartilage from the group receiving a medium testosterone dose for seven days (b); note that the cartilage has been completely replaced by bone)

The authors of this study concluded several key points. First, testosterone treatment at high or even medium doses over a prolonged period completely redirected cartilage formation, meaning cartilage stopped growing and proliferating. This effect was largely mediated by increased IGF-1 secretion. Although estrogen may have contributed slightly to ossification, it is unlikely to play a major role. Second, although cartilage volume initially increased compared to controls, it ultimately decreased by the end of the experiment and grew less than the control group. The main conclusion is that high androgen doses can induce cartilage ossification through IGF-1. To further confirm these findings and determine whether testosterone’s effect on ossification is due to anabolic or androgenic action, scientists removed the testes of rats (eliminating estrogen production) and administered a strongly anabolic but weakly androgenic compound with very low estrogen conversion potential at a low dose. Despite the low dose and very low estrogen levels due to castration, the compound still induced strong growth plate ossification, even more than controls. This strongly demonstrates that even with extremely low estrogen, anabolic stimulation can induce severe ossification [31].

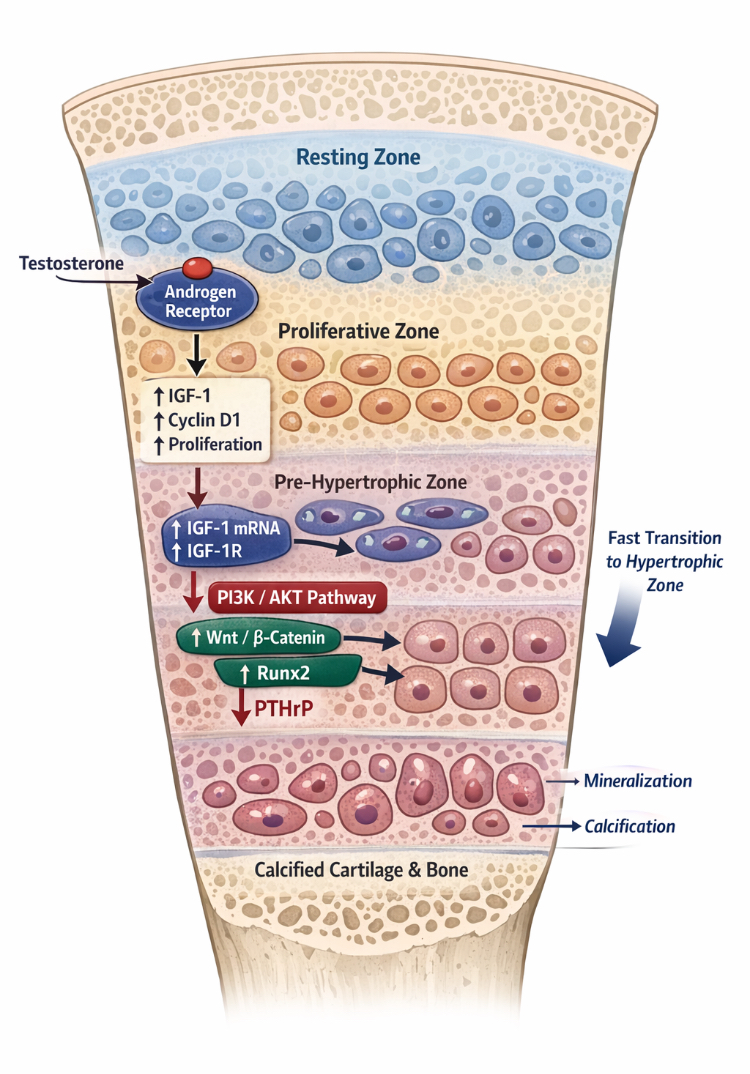

So how do androgens directly stimulate bone maturation independently of estrogens? When testosterone binds to its receptor on chondrocytes, it increases IGF-1 mRNA and IGF-1R expression in the prehypertrophic zone. Elevated IGF-1 in this zone creates a negative feedback loop, reducing PTHrP expression and increasing Wnt-β-catenin and Runx2 through PI3K/AKT activation. This drives prehypertrophic chondrocytes rapidly into the hypertrophic zone, accelerating growth plate and cartilage ossification. Note that androgens also activate IGF-1 in proliferative chondrocytes, increasing proliferation via PI3K/AKT and cyclin D1, but IGF-1 activation in the prehypertrophic zone is much stronger than PI3K/AKT activation, leading to greater Wnt-β-catenin and Runx2 activation [66,67,68,30,49]. It is unclear whether IGF-1 first activates Runx2, which then reduces PTHrP, or if PTHrP is directly suppressed first, allowing Runx2 activation once its inhibitor is removed.

(Figure 4: Schematic illustration of how androgens may theoretically accelerate bone maturation. Note: the image was generated using AI but is based on strong scientific evidence; sources can be verified)

Based on this evidence, it is logical to conclude that androgens have a direct ability to accelerate bone maturation, at least in rodents. There is no biological reason to deny the possibility of the same occurring in humans, especially since the growth plate dynamics in rodents are very similar to those in humans. Furthermore, many human studies using anabolic steroids that do not aromatize into estrogen still cause bone maturation. It is also clear and strongly supported by evidence that the use of aromatase inhibitors is unlikely to prevent the negative effects on bone maturation. How could there be a biological reason supporting this idea if even a very potent estrogen receptor antagonist did not prevent this effect at all? This is even before considering the fact that recent meta-analyses have shown that aromatase inhibitors are ineffective in delaying bone maturation even without any other compounds. Imagine the results if they were combined with a very strong stimulator of cartilage maturation, such as anabolic-androgenic steroids (AAS) [32]. As for the effectiveness of external androgen injections in increasing local IGF-1 in the growth plate, studies are somewhat contradictory; for example, a study on hypophysectomized rats found that testosterone injections for ten days did not increase the sensitivity of IGF-1 receptors or IGF-1 levels in the growth plates, but they did slightly increase growth hormone receptors [33]. Also, in another study on castrated rats, external testosterone injection failed to stimulate IGF-1 or its receptors in the growth plates [34]. In another study on embryonic rat bones, scientists tried using very high doses of either Anavar or testosterone, yet it did not stimulate growth or increase IGF-1, and even deleting androgen receptors did not affect the longitudinal growth of the bones [35]. The reason for the contradiction between in vivo and in vitro studies may be due to different measurement methods; for instance, in vivo studies measure expression across the entire plate, while in vitro studies measure expression in each zone, which could be a logical reason, or it could be due to differences in dosages. Based on the evidence I have presented, it is illogical to assume that androgens will stimulate longitudinal growth and increase your final height, as there is almost no study, whether on animals or humans, that suggests this; in fact, most studies indicate that they have no effect on final height, and if one exists, it would be purely negative. The fact that rodent studies found androgens to be a potent stimulator of bone maturation, and the use of an extremely powerful estrogen receptor inhibitor did not prevent any of this effect, is suspicious and raises doubts as to whether the use of an aromatase inhibitor would actually be sufficient to prevent these negative effects. It must be understood that the response of all mammals to sex hormones is highly interconnected, so there is no logical reason to assume that the negative effects seen in rodents would not appear in humans. Based on this evidence, caution is recommended against the misuse of anabolic steroids during puberty.

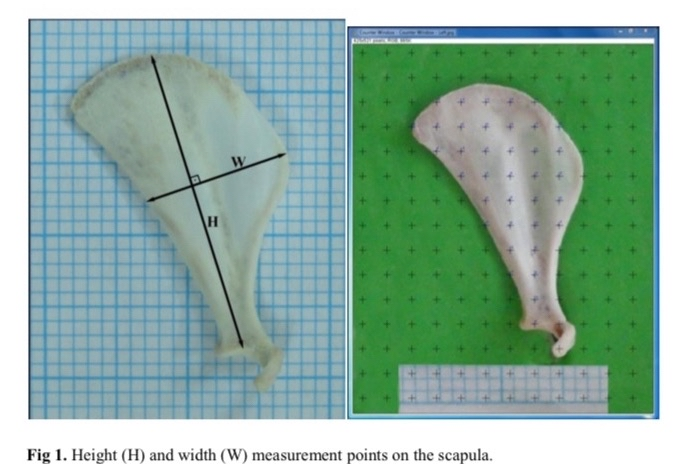

Now what about the growth of the clavicle or the growth of the body frame in general? For a strange and misunderstood reason, people believe that the clavicle responds magically to androgens, unlike long bones, and that androgens are a powerful stimulant for the clavicle, but this is incorrect and there is no evidence to support it. Some might say it is important for clavicle growth because men have wider clavicles than women, and this is true, but men also have longer spines and legs, so does this mean the difference is caused by androgens? No. The clavicle and the growth plates in the spine or legs have similar methods of longitudinal growth, as both are formed through endochondral ossification. Based on this, it is completely illogical to assume that the clavicle will respond in a different or magical way, or for some to believe that the growth plates in the clavicle possess more androgen receptors, even though I have shown that high activation of androgen receptors in the growth plate is actually harmful. To answer this question, there is actually a study on rats, but the study was not on the clavicle bones; rather, it was on the scapula (shoulder blade). The scapula connects directly with the clavicle, and both share very similar longitudinal growth mechanisms, so it is logical that whether androgens affect them negatively or positively, the same would happen to the clavicle. Scientists used male and female rats and injected them with a DHT derivative called "Methenolone," and the results? Unfortunately, they were no different from the results for long bones, as the compound led to a shortening of the scapula compared to the control group in the male category, while doing the opposite in females [36].

(Fig 5: An illustration showing how scientists measured the scapula length in rats to determine the effect of androgenic hormones.)

Now, what about the increase in facial and body bone size, or even bone density? There is a wealth of data to discuss this in detail. We will first address human findings, then animal studies, then genetically modified animals, and finally in vitro models. First, I will not speak at length about bone density because, according to the latest systematic review of 7 randomized controlled trials regarding the effectiveness of testosterone injections for increasing bone density in men, it was found to be useless [37]. In fact, another study found that administering an aromatase inhibitor plus testosterone decreased bone density compared to the control group [38]. Interestingly, another study tested DHT injections in healthy individuals and found that it decreased bone density [39]. Another study found that external testosterone injections might increase bone density in women, but this effect is indirect, occurring through the increase in muscle mass which then increases bone density because increased muscle volume increases mechanical tension on the skeletal system [40]. This lack of effectiveness does not seem limited to therapeutic replacement doses; even high doses in transgender individuals did not show a clear increase in bone density [41]. In another study on healthy men taking very high amounts of anabolic steroids for muscle building, bone formation markers did not differ before the cycle. In fact, bone resorption markers increased slightly, while bone formation markers did not rise [42]. In another study on healthy elderly men, participants were divided into two groups: one receiving DHT and another receiving a placebo. Although the DHT group achieved blood DHT levels twenty times higher than the control, bone formation markers did not increase at all. However, when participants were given a testosterone agonist (where estrogen increases), bone formation markers rose, leading researchers to conclude that the effects of androgens on bone formation result from conversion to estrogen, at least in mature bone [43]. In another study on women using high doses of various androgenic hormones for gender transition, bone density did not significantly increase after 3 years of use [44]. Thus, there is no robust study supporting the idea that administering androgens will significantly increase bone density; if it does increase, the effect is either due to increased muscle mass increasing mechanical load or through conversion to estrogen. Although these studies speak of bone density rather than size, the results are the same for studies examining bone size (periosteal expansion). In female-to-male transgender individuals, the use of high-dose androgenic hormones for 5, 15, or even 25 years had no effect on increasing bone diameter or periosteal expansion [45]

It is unfortunate to note that studies addressing the effect of androgenic hormones on facial bone growth are very scarce, with only one study available that suffers from clear methodological weaknesses. This study was conducted on boys with delayed puberty, where six of them received a low dose of testosterone and were compared with a control group of seven healthy boys. The results showed no difference in the length of the anterior or posterior cranial base or the total length of the cranial base, nor was there any difference in upper midface length, while a slight increase in lower face length was recorded compared to the control group, along with a significant decrease in total anterior face length growth compared to the control, in addition to a slight increase in mandibular width. As for the length of the lower jaw (mandible), it appeared to have decreased in both groups, which is biologically impossible, strongly indicating a measurement error. Overall, the study did not show real significant differences in facial bone growth between the two groups except for slight changes in mandibular width and lower face length. The study suffers from severe methodological limitations that make its results unreliable, most notably the extremely small sample size which makes findings highly sensitive to individual variation, the lack of randomization and presence of selection bias, the absence of a placebo group, and the short follow-up period limited to only one year, which prevents judging the final growth outcome. Furthermore, the participants were already suffering from androgen deficiency due to delayed puberty; therefore, administering testosterone may have only led to a temporary acceleration of growth without any effect on the final structure, similar to the effect of androgens on final body height where they only accelerate growth without a real increase. It is likely that the same occurred for the lower jaw. Additionally, the study was observational and non-blinded, and the two groups were not matched in terms of chronological or bone age but only by height. A weak measurement method relying on 2D images with manual identification of measurement points was used, a method highly sensitive to errors, evidenced by the illogical result of decreased mandibular length, confirming that measurement errors played a major role in the results [47].

There is also a study on women with androgen overproduction where their skull width was compared to that of normal women and this serves as a suitable model to determine if very high levels of androgens can truly cause periosteal expansion as skull width would be significantly affected by periosteal size but head circumference was not significantly different between the groups meaning that androgen overproduction from birth did not affect periosteal expansion at least in the skull [46]. Now to discuss another important topic which is the studies linking testosterone levels with facial masculinity as this is very crucial and let us discuss the two most important studies where the first was conducted on boys aged 12 to 18 to see how testosterone correlates with a masculine face and interestingly the width and length of the nose chin narrowness a wide mandible and a prominent forehead were strongly associated with blood testosterone levels meaning as testosterone increased the prominence of these features increased and the correlation was so strong it is unlikely to be a coincidence however the correlation between testosterone levels and brow bone prominence or cheekbone prominence was nearly zero meaning that rising testosterone levels had no association with increasing the size of these bones which is frankly strange especially regarding the brow bone and I will provide an explanation for this later and the strangest part of this study was that androgen receptor sensitivity was not associated with masculine features when scientists divided participants based on high or low sensitivity they found no difference in masculine features suggesting that testosterone may have caused the prominence of some masculine features indirectly not necessarily through direct androgen receptor binding perhaps through higher conversion to DHT within the bone although there is no evidence for this [48]. I have a major issue with this study because it does not answer all questions whether testosterone levels correlated with masculine features because it rose during puberty and then began its effect or because it was high during pregnancy and influenced masculine features so when it rose during puberty it appeared as if the effect was caused then while it was actually due to fetal exposure which is crucial because most sex hormone effects manifest before birth [50]. To answer this question it is logical to have a study that measures umbilical cord testosterone levels before birth follows these individuals until they complete puberty and observes the effect of prenatal testosterone on masculine facial features while simultaneously measuring adult blood testosterone levels and fortunately such a study exists where they took umbilical cord blood samples at birth from 861 children and later took 3D facial images as adults alongside blood samples from 85 males to check the effect of pubertal testosterone and the results showed a very strong correlation between prenatal testosterone levels and masculine features during adulthood though fWHR did not correlate with testosterone levels prenatally or during puberty however the correlation between adult testosterone levels and masculine features was literally zero and not statistically significant meaning the study found that masculine features such as forehead width mandible and chin were primarily linked to prenatal testosterone exposure and levels during puberty had no effect and those with high prenatal testosterone had masculine features while those without did not regardless of their pubertal levels [49]. It is important to mention that testosterone is still somewhat important for normal facial bone growth as shown in rodent studies [51] but this does not necessarily contradict human findings as it appears that masculine features are determined by prenatal testosterone exposure but testosterone during puberty is important to realize the effects predetermined by that prenatal exposure and it does not seem that androgen exposure during growth will have a significant role if you were not exposed to it at birth at least as current studies suggest.

Now we will discuss animal studies because there are excellent studies on this topic where we will first look at the effect of supraphysiological levels of androgens on increasing the size of long bones and then discuss facial bones noting that most of the studies I will mention come from previous research examining the effect of steroids on longitudinal bone growth as they simultaneously observed the effect on transverse growth and all studies are conducted on healthy animals because they best simulate the results likely to occur in healthy humans. For example in the first study the injection of Methenolone which is a DHT derivative led to a reduction in the width of the scapula bone but this negative effect only appeared in males while it enhanced the width of the scapula in females which is the same result found for bone length [36]. Another study looked at the effect of Methenolone on the width of the femur and the same results appeared here as well where the bone width significantly decreased in males and increased in females [12]. Another study found that using the same compound again led to a reduction in the circumference of the radius bone in male rats but increased it in females [14]. Another study also divided a group of healthy 8 week old rats into two groups where one group received a placebo and the second group received a high dose of stanozolol which is a very powerful androgenic compound that does not convert to estrogen and possesses very high anabolic power and low androgenicity and after the end of the experiment the levels of bone formation markers PINP and Osteocalcin were 53% and 34% lower respectively in the group that received the compound compared to the placebo which is considered a significant and noticeable decrease and the total bone area of the knee significantly but slightly decreased by 5% compared to the control with no effect on bone density [52]. In any case there is more than one study that found the effect to be neutral for the bone with neither an increase nor a decrease in bone diameter such as giving high amounts of testosterone which did not affect the width or area of the radius or femur [53,54,55] and other studies also used Deca and Trenbolone and found that they had no effect on the area and size of the femur and radius [13,15,16]. These rat studies relatively agree with human findings where supraphysiological levels of androgens will either slightly but noticeably reduce bone area or have a neutral effect regardless of the dose and compound used whether it is aromatizable or not and to my knowledge there is not a single study that found the use of supraphysiological levels could significantly increase the width of long bones in males.

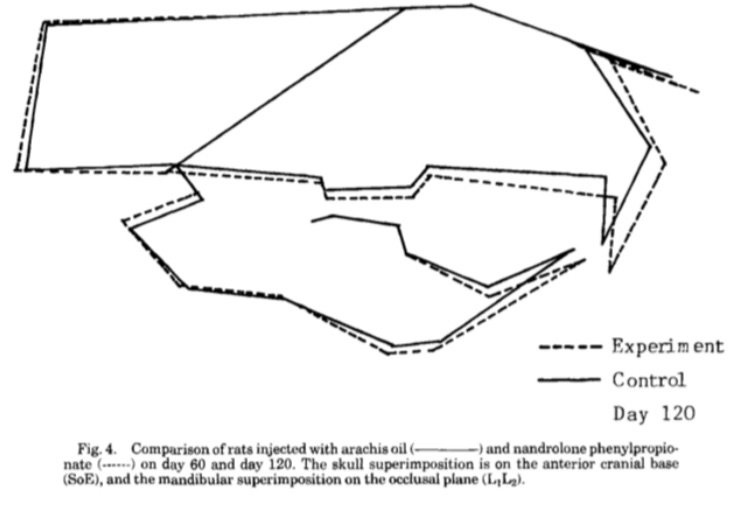

Finally, we will now discuss the most important part of this post, which is the effect of androgenic and anabolic hormones on facial bone growth in rodents. In the first study, 120 female rats aged 4 weeks (just before puberty) were used, where 60 rats were assigned to receive either a placebo or 1 mg of nandrolone phenylpropionate daily, and the effect on facial bones was evaluated after 60 and 120 days. The results were as follows, and I will mention the results after 120 days because they are the most significant: the growth of the cranial base was inhibited because the cranial base is the only bone in the skull that grows through cartilage. The total skull length increased by 4.8%, the total mandibular length increased by 4.36%, and the ramus length increased by 5.7%. These were the significant changes measured, while the rest of the skull parts either remained unchanged or showed slight changes. These results might be disappointing, as they show only slight increases of 4% to 6% after using high doses for a long period. However, this slight growth in the facial bones actually distorted the rats' faces and made them unappealing. How? The upper and lower jaws of the rats grew forward and downward instead of forward and upward. The scientists noted this and concluded it from the measurements taken for the maxilla; even the growth that occurred was mostly downward. A likely explanation for this is that the compound excessively increased the size of the masseter muscle, which pulled the maxilla and mandible downward. It is probable that most of the increases in the size of the mandible and maxilla were not caused by the compound itself, but rather occurred indirectly by stimulating muscle activity and volume, which placed mechanical tension on the bones and stimulated the mandible and maxilla to grow, as it is well known that stimulating the activity of the jaw muscles promotes their growth [57, 58].

(Fig 6: An illustration showing the skull of rats that received the compound compared to the control group after 120 days. The dashed black line represents the experimental group, where you will notice that the maxilla and mandible are slightly longer than the control, but their growth was directed downward, meaning the face becomes longer, or in short, "chopped".)

Now, someone might argue that because supraphysiological levels of androgens inhibited bone growth in males but enhanced it in females, it is logical to assume that even the slight stimulation seen in females would manifest as inhibition in males. However, the answer is no, and fortunately, there is another study with the same design that used both male and female rats. The study design involved male and female rats at 21 days old, the period before puberty, who were given the compound for six weeks to test the effect during the rats' fastest possible growth period. The rats were divided into three groups: the first received a placebo, the second received a therapeutic dose of 1 mg/kg/w of Nandrolone, and the third received a massive dose of 10 mg/kg/w to simulate heavy steroid abuse. The results for the males showed that total mandibular length increased by 1.6% at the low dose but only by 0.6% at the high dose. Ramus length increased by 1.9% at the low dose but did not increase at all at the high dose. Skull length increased by 1.6% at the low dose and 1.1% at the high dose. Skull width increased by 0.43% at the low dose and decreased by 0.5% at the high dose. Midface length increased by 1.22% at the low dose and 1.36% at the high dose, while midface width increased by 2.9% at the low dose and 2.4% at the high dose. For females, the response was significantly higher, with most increases ranging between 3% and 3.5%, nearly double the increase seen in males. While higher doses sometimes gave higher increases in females, the overall effect remained very limited for both sexes [61]. There was another issue: the compound caused unbalanced growth leading to a Class II malocclusion, where the maxilla becomes longer or more forward-projecting. Since the effect was limited, this deformity might not be visible to the naked eye. We conclude that females respond better because they have lower baseline androgen levels, meaning their receptors are not saturated. Evidence of rapid saturation in males is seen in the fact that a tenfold increase in dose provided no additional benefit, and sometimes even less [59, 60]. Furthermore, even slight growth is unappealing; the maxilla grows more than the mandible, and the excessive increase in masseter muscle volume seems to stimulate both jaws to grow downward instead of upward. Researchers suggested the growth was likely an indirect result of muscle volume. As steroids increase masseter, temporal, and pterygoid muscle size, the bone responds to increased mechanical tension through appositional growth, supported by Wolff's Law [62]. Most growth occurred in bones connected to these muscles. Human studies support this, showing testosterone increases bone density indirectly via muscle mass and mechanical load [40]. Similar effects are seen with Anavar, where bone density only increases after muscle mass increases [63]. I believe growth resulted from both direct and indirect factors. The downward maxilla growth is explained by excessive muscle mass pulling the jaw down. Why the maxilla protrusion? A logical explanation is that androgens accelerated maxillary suture growth while simultaneously stimulating closure. Physiological doses of DHT induce complete closure of the sagittal suture in rats by increasing Transforming Growth Factor Beta-1 (TGF-β1). In that study, 5 nM of DHT enhanced bone cell proliferation by 20%, but 1000 nM actually resulted in less proliferation, confirming saturation. While it is unclear if facial sutures respond exactly like cranial sutures, high androgen levels likely bind to facial receptors and accelerate fusion, potentially limiting the effectiveness of mechanical expansion techniques [64, 65]. How do we know this applies to humans? A study on human mandibular-derived bone cells aligns with the rat data. The highest response occurred at 5-10 ng/mL, increasing DNA synthesis by 50%. A tenfold increase in dose caused the response to drop to 20% because bone cells downregulated their androgen receptors by 40%. Since the S-phase makes up 40% of the cycle, a 50% increase in activity translates to a 20-30% increase in overall proliferation, very close to the results in rats [69]. Why did high doses cause Class II despite saturation? Perhaps the sutures of the dura mater are more sensitive to DHT, causing them to mature and fuse even faster. If DHT drives cells toward differentiation before sufficient proliferation, it likely causes faster calcification. This remains a strong hypothesis, and caution is advised.

Thus, I have proven that using steroids to improve facial aesthetics is completely useless. There is absolutely no evidence supporting their use, and all existing evidence refutes their effectiveness. Therefore, the burden of proof lies with the claimant; they must provide evidence to support their beliefs or stop promoting them. Some might now think that since androgens moderately stimulate osteoblast activity, their use should theoretically be beneficial when combined with "bone smashing" or mechanical loading methods in general, right? Well, no. I have bad news: androgens completely negate the effectiveness of mechanical tension in periosteal expansion. I literally mean completely; in fact, they cause a loss of bone formation on the periosteal surface instead of building it. For example, in a study on adult mice, scientists castrated the mice and applied mechanical loading to their bones. In the control group (mechanical loading without castration), the bone formation rate on the periosteal surface increased by 170%. In the castrated mice, the bone formation rate on the periosteal surface increased exponentially by 732%. However, administering testosterone completely inhibited the increase in bone formation on the periosteal surface, and giving DHT combined with mechanical loading reduced the bone formation rate by 85% compared to the control. These are very interesting results; administering androgenic hormones literally cancelled the response entirely. This is not the only study to reach this conclusion; another study that knocked out androgen receptors in male mice found that mechanical loading increased the periosteal bone formation rate by 320% compared to only 120% in the control group. This is a huge difference. When bone is subjected to mechanical loading, NO and COX-2 activity increases so osteocytes can communicate, blood vessels can dilate, and NO can increase CAMKII, which enters the nucleus to degrade SOST so the Wnt/β-catenin pathway can activate. Without these steps, mechanical loading is nearly useless because the main pathway does not work. What is the link to androgens? When scientists exposed bone to mechanical loading, they found that the androgen receptor (AR) completely prevented the increase in NO and reduced the COX-2 increase by 50%. This means the AR prevented the suppression of SOST typically caused by mechanical loading, thus Wnt did not rise and bone formation did not trigger. Furthermore, after massive mechanical loading on the bone (such as bone smashing), rapid woven bone is formed due to the damage. In this stage, NO is crucial for dilating blood vessels and transporting nutrients. Since the AR completely inhibited NO during physiological mechanical loading, it is likely the same happens during extreme mechanical injury, where the inhibition of NO significantly prevents the formation of new woven bone [70, 71, 72, 73]

Now we will discuss the effect of genetic modification of the Androgen Receptor (AR) through hyperactivity and its impact on body bone mass and skull bones, as the results here are very interesting. In one study, scientists modified mice so that only mature osteocytes overexpressed AR, and the results were somewhat strange; they noticed a 50% decrease in Osteocalcin, which is a marker for bone formation. There was no difference in skull width between normal and genetically modified mice, which is logical since the modification targeted mature cells located inside the bone. However, the internal bone volume was significantly lower, and the cortex was thinner because bone formation on the endosteal surface was inhibited by androgen hyperactivity, meaning the bone was slightly thinner in male mice. Interestingly, all these negative effects appeared only in males, which may partially explain previous findings regarding the effect of androgen administration on bone diameter in males versus females. Another study modified mice to produce AR in periosteal progenitor cells, and the results were very intriguing; the skull bone was significantly wider in the experimental group, but only in males since females have androgen levels too low to benefit from the modification. At the same time, the long bones were not wider but actually thinner. This may seem strange, but why did it happen? Scientists conducted a third study, again modifying mice to overexpress AR in periosteal cells, and the results were as follows: bone formation on the periosteal surface of the parietal bone was unaffected, but the frontal bones significantly increased in size. In the lab, when they isolated parietal cells and exposed them to DHT, proliferation and mineralization decreased. However, in cells from the frontal bone, the rate of bone formation and matrix calcification increased. Why are these results contradictory? The difference lies in the embryonic origin: the parietal bone is derived from the mesoderm, whereas the frontal bones are derived from the neural crest. These results explain why overexpressing androgens in progenitor cells increases periosteal bone formation in the frontal bone but not in long bones [74, 75, 76].

So, why this difference? The answer is not fully known, but it has been decisively documented. Modifying mice to overexpress androgen receptors increased the area of bones derived from the neural crest (all facial bones without exception are derived from the neural crest), but for bones derived from the mesoderm, it had no effect on periosteal expansion and inhibited internal bone formation, thus slightly decreasing bone volume. This also explains why administering androgens in some studies slightly inhibited bone expansion in long bones while slightly increasing bone formation in facial bones. I regret to say that this will not happen without genetic modification because the receptors are already saturated, as I showed previously. Studies indicate that anabolic hormones increase facial dimensions very slightly in males while slightly more in females because they have more available receptors, whereas they may also decrease the circumference of long bones by inhibiting internal expansion through binding with available receptors.

Now we will discuss the effect of androgens on bone cell proliferation in the laboratory. For example, in a study on osteoblasts derived from the cranial vault, meaning from the neural crest and specifically from the periosteum, using proliferating undifferentiated cells exposed to DHT, it was found that bone cell proliferation increased in the short term, but was inhibited in the long term. The reason was that DHT inhibited the MAP pathway, including ERK1/2 and ELK-1. Does this contradict the in vivo results where AR overexpression increased bone formation in neural crest derived bones? Not necessarily. First, DHT inhibited proliferation, not differentiation. It is possible that in vivo overexpression enhanced osteoblast differentiation while inhibiting proliferation, thus maturing and completing the bone shape faster without necessarily increasing the final size. Another very logical explanation is that in vivo androgen receptor activation is pulsatile. Even with AR modification, the rat's body still produces testosterone in pulses, so the receptor is activated intermittently and does not produce a negative effect, whereas the study showed inhibition after continuous long term exposure. Another study on mature osteocytes found that androgens significantly increased IGF-1 mRNA in the short term within 72 hours. However, in a study on osteoblasts stimulated with PGE2 to increase IGF-1, the effect of DHT was complex and strange. While PGE2 increased IGF-1 and bone cell proliferation, the addition of DHT inhibited the IGF-1 increase by suppressing the C/EBPδ gene, which is a gene that stimulates IGF-1. I will not present more studies because they are numerous and each provides different results, as the outcome depends heavily on several factors: 1. The medium in which the cells are cultured and whether anything else affects the AR pathway. 2. The type of cell used and whether it is genetically modified. 3. The embryonic origin of the cells, whether from the neural crest or mesoderm, and whether they are mature osteocytes or undifferentiated progenitors. 4. The duration of exposure, which appears to be very critical. Therefore, contradictory results do not imply scientific inaccuracy, but simply reflect differences in experimental conditions [77, 78, 79, 80, 81]

Summary: It does not appear that androgens possess the potential to increase final height or even the length of the clavicle. If the AR receptor is available for binding in chondrocytes, it will increase IGF-1R in pre-hypertrophic chondrocytes, thereby activating the PI3K/Akt pathway, facilitating the entry of β-catenin into the nucleus, and activating the genetic program for cartilage calcification. Furthermore, studies do not support its use for the purpose of improving facial aesthetics, as it may inhibit the bone's response to mechanical tension. Therefore, caution is advised against using anabolic steroids without understanding their true effects.

1. Sybert VP. Adult height in Turner syndrome with and without androgen therapy. J Pediatr. 1984 Mar. 2. Wilson DM et al. Oxandrolone therapy in constitutionally delayed growth and puberty. Bio-Technology General Corporation Cooperative Study Group. Pediatrics. 1995 Dec. 3. Oxandrolone treatment of short stature: Effect on predicted mature height. 4. Lenko HL et al. Acceleration of delayed growth with fluoxymesterone. Acta Paediatr Scand. 1982 Nov. 5. Oxandrolone in constitutionally delayed growth, a longitudinal study up to final height. 6. Marti-Henneberg C et al. Oxandrolone treatment of constitutional short stature in boys during adolescence: effect on linear growth, bone age, pubic hair, and testicular development. J Pediatr. 1975 May. 7. A double-blind, placebo-controlled comparison of letrozole to oxandrolone effects upon growth and puberty of children with constitutional delay of puberty and idiopathic short stature. 8. Long-term results of treatment with low-dose fluoxymesterone in constitutional delay of growth and puberty and in genetic short stature. 9. Bassi F et al. Oxandrolone in constitutional delay of growth: analysis of the growth patterns up to final stature. J Endocrinol Invest. 1993 Feb. 10. Schroor EJ et al. The effect of prolonged administration of an anabolic steroid (oxandrolone) on growth in boys with constitutionally delayed growth and puberty. Eur J Pediatr. 1995 Dec. 11. Influence of norethandrolone on the stature of short children. 12. Bozkurt I et al. Morphometric evaluation of the effect of methenolone enanthate on femoral development in adolescent rats. 13. Yalcin H. Morphometric effect of nandrolone decanoate used as doping in sport on femur of rats in puberty period. 14. Bozkurt I et al. Morphometric evaluation of the effect of methenolone enanthate on humeral development in adolescent rats. 15. Yalcin H. Morphometric effect of nandrolone decanoate used as doping in sport on femur of rats in puberty period. 16. Sari A, Lök S. The Effects of Trenbolone Supplementation on the Extremity Bones in Running Rats. Selcuk University. 17. The CAG repeat polymorphism within the androgen receptor gene and maleness. 18. Wiren KM et al. Targeted overexpression of androgen receptor in osteoblasts: unexpected complex bone phenotype in growing animals. Endocrinology. 2004 Jul. 19. Butler MG et al. Androgen receptor (AR) gene CAG trinucleotide repeat length associated with body composition measures. J Assist Reprod Genet. 2015 Jun. 20. Campbell BC et al. Androgen receptor CAG repeats and body composition among Ariaal men. Int J Androl. 2009 Apr. 21. Growth factor regulation of human growth plate chondrocyte proliferation in vitro. 22. Schwartz Z et al. Gender-specific, maturation-dependent effects of testosterone on chondrocytes in culture. Endocrinology. 1994 Apr. 23. Nasatzky E et al. Sex-dependent effects of 17-beta-estradiol on chondrocyte differentiation in culture. J Cell Physiol. 1993 Feb. 24. Rapid membrane responses to dihydrotestosterone are sex dependent in growth plate chondrocytes. JSBMB. 25. 1,25(OH)2D3 and dihydrotestosterone interact to regulate proliferation and differentiation of epiphyseal chondrocytes. 26. Sexual dimorphism of growth plate prehypertrophic and hypertrophic chondrocytes in response to testosterone requires metabolism to dihydrotestosterone (DHT)

27. Gunther DF et al. Androgen-accelerated bone maturation in mice is not attenuated by Faslodex, an estrogen receptor blocker. Bone. 2001 Apr. 28. McKeage K et al. Fulvestrant: a review of its use in hormone receptor-positive metastatic breast cancer. Drugs. 2004. 29. Gunther DF et al. The effects of the estrogen receptor blocker, Faslodex (ICI 182,780), on estrogen-accelerated bone maturation in mice. Pediatr Res. 1999 Sep. 30. Maor G et al. Testosterone stimulates insulin-like growth factor-I and insulin-like growth factor-I-receptor gene expression in the mandibular condyle. Endocrinology. 1999 Apr. 31. Silberberg R, Silbe M. Epiphyseal growth and development in mice following administration of a protein-anabolic steroid. 32. Liu J et al. Treatment of Short Stature with Aromatase Inhibitors: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Horm Metab Res. 2021 Jun. 33. Zung A et al. Testosterone effect on growth and growth mediators of the GH-IGF-I axis in the liver and epiphyseal growth plate of juvenile rats. J Mol Endocrinol. 1999 Oct. 34. Phillip M et al. Effect of testosterone on insulin-like growth factor-I (IGF-I) and IGF-I receptor gene expression in the hypophysectomized rat. Endocrinology. 1992 May. 35. Androgen Receptor Modulation Does Not Affect Longitudinal Growth of Cultured Fetal Rat Metatarsal Bones. 36. Özdemir M et al. Morphometric effect of methanolone enanthate on scapula in adolescent rats. 37. Junjie W et al. Testosterone Replacement Therapy Has Limited Effect on Increasing Bone Mass Density in Older Men: a Meta-analysis. Curr Pharm Des. 2019. 38. Finkelstein JS et al. Gonadal steroid–dependent effects on bone turnover and bone mineral density in men. 39. Idan A et al. Long-term effects of dihydrotestosterone treatment on prostate growth in healthy, middle-aged men: a randomized trial. Ann Intern Med. 2010. 40. Douchi T et al. Relationship of androgens to muscle size and bone mineral density in women with polycystic ovary syndrome. Obstet Gynecol. 2001 Sep. 41. Mueller A et al. Effects of intramuscular testosterone undecanoate on body composition and bone mineral density in female-to-male transsexuals. J Sex Med. 2010 Sep. 42. The Effect of Supraphysiological Doses of Anabolic Androgenic Steroids on Collagen Metabolism. 43. Meier C et al. Recombinant human chorionic gonadotropin but not dihydrotestosterone alone stimulates osteoblastic collagen synthesis in older men. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2004 Jun. 44. Delgado-Ruiz R et al. Systematic Review of the Long-Term Effects of Transgender Hormone Therapy on Bone Markers and Bone Mineral Density. J Clin Med. 2019. 45. Wiepjes CM et al. Bone geometry and trabecular bone score in transgender people before and after hormonal treatment. Bone. 2019 Oct. 46. Webb E et al. Quantitative brain MRI in congenital adrenal hyperplasia. 47. Verdonck A et al. Effect of low-dose testosterone treatment on craniofacial growth in boys with delayed puberty. Eur J Orthod. 1999 Apr. 48. Marečková K et al. Testosterone-mediated sex differences in the face shape during adolescence: Subjective impressions and objective features. 49. Wang Y et al. IGF-1R signaling in chondrocytes modulates growth plate development by interacting with the PTHrP/Ihh pathway. J Bone Miner Res. 2011 Jul. 50. Cohen-Bendahan CC et al. Prenatal sex hormone effects on child and adult sex-typed behavior: methods and findings. Neurosci Biobehav Rev. 2005 Apr. 51. Reis CLB. Testosterone suppression impacts craniofacial growth structures during puberty: An animal study. 52. Nebot E et al. Stanozolol Decreases Bone Turnover Markers, Increases Mineralization, and Alters Femoral Geometry in Male Rats.

53. Kilci A, Lok S. Morphometric effects of testosterone supplementation on certain extremity bones in young swim-trained rats. 54. The morphometric effects of testosterone, used as a doping agent, on the humerus and femur of pubescent male and female rats. 55. Does the use of Testosterone Enanthate as a Form of Doping in Sports Cause Early Closure of Epiphyseal in Bones? 56. Rönning O et al. Effect of Nandrolone Phenylpropionate on the Bone of Young Rats. University of Turku. 57. Effects of the anabolic steroid nandrolone phenylpropionate on craniofacial growth in rats. 58. Kiliaridis S et al. The relationship between masticatory function and craniofacial morphology. Eur J Orthod. 1985. 59. Changes with age in levels of serum gonadotropins, prolactin, and gonadal steroids in prepubertal male and female rats. 60. Effects of anabolic steroids on skeletal muscle mass during treatment of athletes. Exer Sports Med 1985. 61. Anabolic steroids and craniofacial growth in the rat. 62. Enlow DH. Wolff's law and the factor of architectonic circumstance. 63. Murphy KD et al. Effects of long-term oxandrolone administration in severely burned children. Surgery. 2004 Aug. 64. Yu P et al. The role of transforming growth factor-beta in the modulation of mouse cranial suture fusion. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2001. 65. Lin IC et al. Dihydrotestosterone stimulates proliferation and differentiation of fetal calvarial osteoblasts and dural cells and induces cranial suture fusion. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2007 Oct. 66. Parathyroid hormone-related peptide (PTHrP) inhibits Runx2 expression through the PKA signaling pathway. 67. Wang L et al. Thyroid hormone-mediated growth and differentiation of growth plate chondrocytes involves IGF-1 modulation of beta-catenin signaling. J Bone Miner Res. 2010 May. 68. Guo X et al. The Wnt/beta-catenin pathway interacts differentially with PTHrP signaling to control chondrocyte hypertrophy and final maturation. 69. Kasperk C et al. Skeletal Site-Dependent Expression of the Androgen Receptor in Human Osteoblastic Cell Populations. 70. Tomlinson RE et al. Nitric oxide-mediated vasodilation increases blood flow during the early stages of stress fracture healing. J Appl Physiol. 2014. 71. Androgen receptor disruption increases the osteogenic response to mechanical loading in male mice. 72. Sinnesael M et al. Androgens inhibit the osteogenic response to mechanical loading in adult male mice. Endocrinology. 2015 Apr. 73. Buck HV et al. Nitric oxide contributes to rapid sclerostin protein loss following mechanical load. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2024. 74. Bone vs. fat: Embryonic origin of progenitors determines response to androgen in adipocytes and osteoblasts. 75. Wiren KM et al. Targeting of androgen receptor in bone reveals a lack of androgen anabolic action and inhibition of osteogenesis. Bone. 2008 Sep. 76. Wiren KM et al. Targeted overexpression of androgen receptor in osteoblasts: unexpected complex bone phenotype in growing animals. Endocrinology. 2004 Jul. 77. Effects of Gonadal and Adrenal Androgens in a Novel Androgen-Responsive Human Osteoblastic Cell Line. 78. Wiren KM et al. Androgen inhibition of MAP kinase pathway and Elk-1 activation in proliferating osteoblasts. J Mol Endocrinol. 2004 Feb. 79. Wiren KM et al. Signaling pathways implicated in androgen regulation of endocortical bone. Bone. 2010 Mar. 80. McCarthy TL et al. Androgen receptor activation integrates complex transcriptional effects in osteoblasts, involving the growth factors TGF-β and IGF-I. Gene. 2015. 81. Effects of Androgens on the Insulin-Like Growth Factor System in an Androgen-Responsive Human Osteoblastic Cell Line.

Thank u guys for reading, i have been working in this for month straight, please share some love and we can debate ofc