Alexanderr

Admin

- Joined

- Mar 5, 2019

- Posts

- 22,473

- Reputation

- 47,959

I've got this very nice quote in one of my personal documents:

The "self" is not a static noun. It is the cumulative, emergent property of its own actions. You are the sum of your "dos.”

Yes, it makes for a good quote on a wall, but here's why its closer to biological reality than you might think.

Who are you? No, who are you really? Are you just your name, birthplace or social security number? No? Maybe you define yourself in relation to others. You're someone's brother, a son, a friend or partner (lol no).

See, I adopt a different worldview. As I see it, you are those policies your system executes by default. In simpler words, you are that which you do, on average.

This change of framing is important. Most people identify themselves by their nouns, "I'm a cook, I'm a software developer, I'm a dad or I'm a gamer, etc", this measures you by the verbs. "I cook, I do software developing, I raise my children or I play videogames".

This is important because it's much closer aligned to how our biology actually operates. There's no way (mechanistically) for your brain to run on a label, it runs on encoded actions given certain triggers.

For example, you come back from school, you're bored (trigger), the system defaults to "pick up phone, scroll social media" (action), until you realize you still gotta make your homework (termination). Or, you feel hungry (trigger), so your system defaults to "check the fridge" (action), until you've eaten and feel satisfied (termination).

These moves are encoded in your synapses, a network of connected neurons, with a particular pattern firing whenever you're doing anything.

All of your habits, ALL of them, are merely the sum of action bundles you've learnt to take given some context.

The wider implication here is: Action comes first. The “self” is what remains once those actions repeat.

Consequently, any and all advice given without a concrete set of actions to take, given a certain situation might as well be useless.

This flips the usual teaching model on its head

Most instruction tries to do this:

But the real path is:

Okay, but why should I care, @Alexanderr?

Because until you embody this truth, you’ll keep mistaking understanding for change -- and wonder why nothing sticks.

But I reckon this isn't news to a lot of you. You know. You know your habits define who you are, but you cannot seem to change them. You feel trapped by the parts of you that won't listen to reason. Like a ball endlessly trying to roll up a hill but mercilessly brought down by gravity.

See, I didn’t set out to write this as a drug thread. I set out to understand why change keeps undoing itself.

May I here introduce you to,

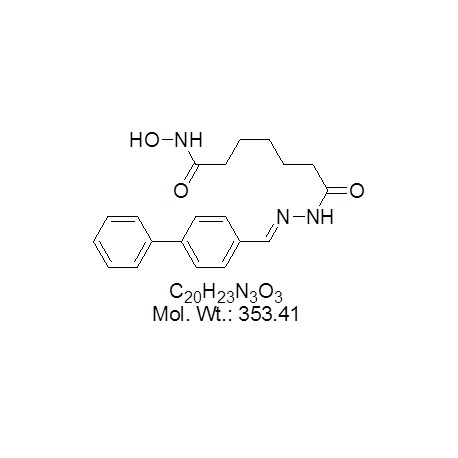

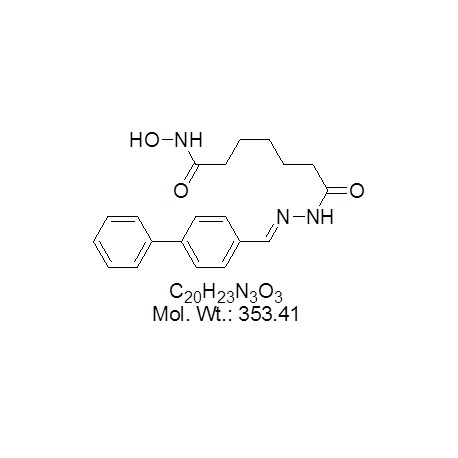

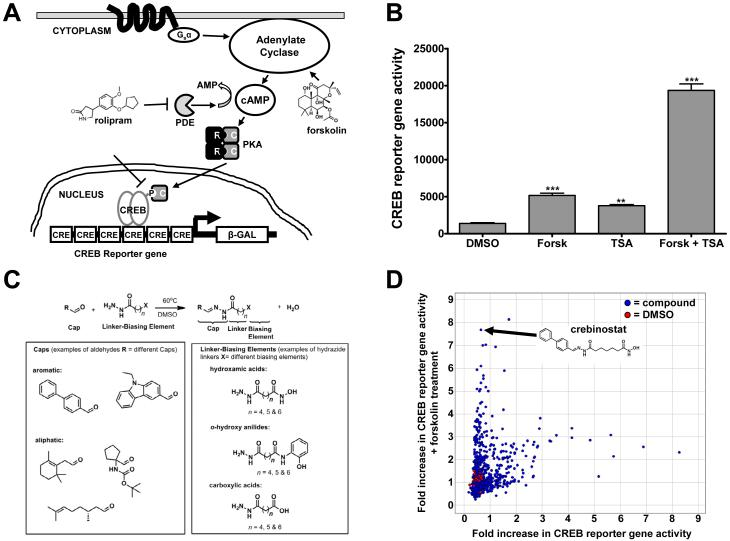

CREBINOSTAT

So, you think I'm introducing you to a miracle drug? I'm not. But here's why it's interesting anyway:

See, the problem for most people is that they can change any one of their moves any given day, the problem is that they don't stick. You go to the gym one day, but the action doesn't stick. You eat healthy one day, but the practice doesn't stick. Why is this?

Because evolution never wanted the (adult) human brain to be one that deviates from a stable state easily. It prioritized changing easily and changing quickly in early youth, but being efficient and stable nearing or upon adulthood. Meaning, if your current state is just enough to survive and reproduce, it's a-okay to evolution.

The implications here being that for you to change, meaningfully, you need to, (using our ball stuck on a U-shaped curve analogy) either:

1. Add massive energy

Trauma, ecstasy, crisis, obsession

-> brute-force shove over the ridge

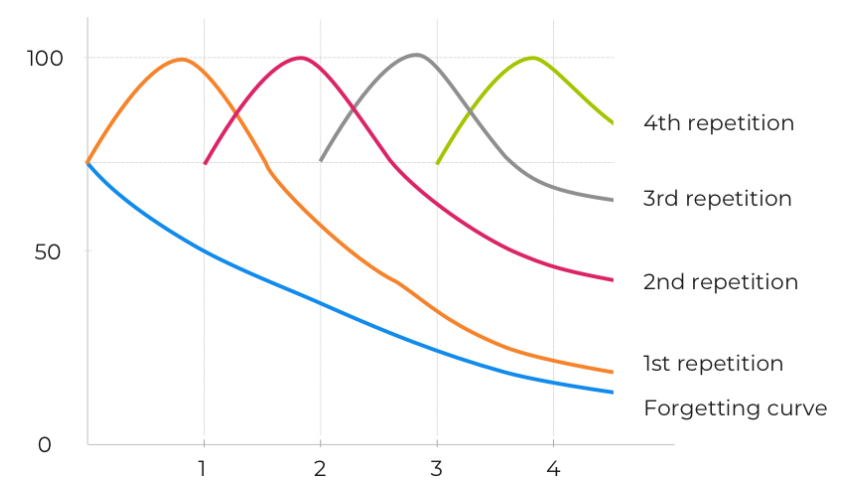

2. Sustain repeated pushes

Slow learning, repetition, scaffolding

-> gradually reshape the basin

3. Change the landscape itself

Alter plasticity, consolidation, or stability parameters

-> same push now travels farther

Most adult change fails because people try #1 briefly or #2 inconsistently, while the system is actively defending #0: stability.

#3 is where Crebinostat comes in.

Crebinostat does not give the ball more force.

It does not create new hills.

It subtly:

How? By lowering the bar for you brain to encode a memory, and thus not forget it.

What people don't understand about our biology and learning is that, forgetting is just as big a part. Your brain forgets all types of irrelevant noise (ex. random license plates) so you can learn or remember what matters (ex. mom's name).

Under normal conditions, the brain only locks in experiences that are clearly tagged as important; usually through strong emotion, novelty, fear, or consequence.

The problem is that there’s no immediate way for the brain to tell what will matter long-term. Your brain doesn’t know that skipping Chipotle is actually good for you.

All it records is a deviation from usual, considers it a fluke, prunes it during sleep, and moves on. Result? The memory trace "skip Chipotle" is never encoded (long term).

The claim here isn’t that one exposure creates a habit, but that a correct action is far less likely to be pruned by the brain -- so you’re not always starting again from square one.

The failure mode for most people isn't in taking a different action, it's in not forgetting it immediately after. This is why Crebinostat is revolutionary.

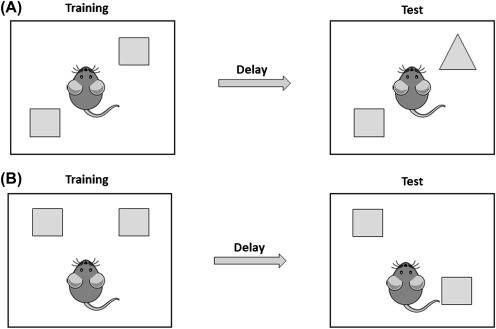

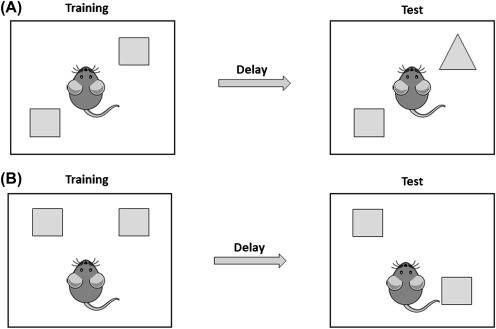

As an example, there was a research study done. Researchers had a mice setup that was designed to test whether a weak learning experience could be converted into a durable long-term memory if the brain’s consolidation (remembrance) machinery was biased in its favor.

Task: A mouse briefly explores two identical objects, and 24 hours later memory is inferred if it preferentially explores a newly introduced object over the familiar one.

Key idea: They used learning examples (identical objects) that were deliberately too weak to produce long-term memory on their own.

Normally:

The answer: A resounding yes -- Crebinostat reliably turned a weak, normally forgettable object-recognition experience into a robust long-term memory.

If I had to answer in one sentence, vividly, what sets Crebinostat apart from all other obscure or grey market drugs I've come across, it's that:

Crebinostat doesn’t push you to learn harder or feel more; it strengthens the brain’s internal scaffolding so that whatever you already did has a much higher chance of not collapsing overnight.

This is extremely rare because most drugs act on moment-to-moment signaling or arousal, whereas Crebinostat targets the slow, normally inaccessible molecular gate that decides whether learning is kept or discarded after the fact.

Examples of every day tasks people's brain generally forgets to store:

But why @Alexanderr, why do you post about an obscure, non-human tested research drug that would be inaccesible anyway?

Because for the first time (as far as I know) it's available to the general public. Although trough some peculiar means. I'll explain.

Someone I consider a friend is hosting a group buy for the drug, it's open until 31st of December. I make no money off of it, but I've been waiting for this opportunity to come by a couple years now [ever since I tried Vorinostat (similar, but less effective for these purposes)].

So I'd feel bad if those of you who are as interested as me in this entire bio-hacking stuff miss out on this (maybe once in a lifetime, idk) opportunity.

You can read and find more here.

Merry Christmas, fellas, I'll keep you updated on this pet project of mine.

The "self" is not a static noun. It is the cumulative, emergent property of its own actions. You are the sum of your "dos.”

Yes, it makes for a good quote on a wall, but here's why its closer to biological reality than you might think.

Who are you? No, who are you really? Are you just your name, birthplace or social security number? No? Maybe you define yourself in relation to others. You're someone's brother, a son, a friend or partner (lol no).

See, I adopt a different worldview. As I see it, you are those policies your system executes by default. In simpler words, you are that which you do, on average.

This change of framing is important. Most people identify themselves by their nouns, "I'm a cook, I'm a software developer, I'm a dad or I'm a gamer, etc", this measures you by the verbs. "I cook, I do software developing, I raise my children or I play videogames".

This is important because it's much closer aligned to how our biology actually operates. There's no way (mechanistically) for your brain to run on a label, it runs on encoded actions given certain triggers.

For example, you come back from school, you're bored (trigger), the system defaults to "pick up phone, scroll social media" (action), until you realize you still gotta make your homework (termination). Or, you feel hungry (trigger), so your system defaults to "check the fridge" (action), until you've eaten and feel satisfied (termination).

These moves are encoded in your synapses, a network of connected neurons, with a particular pattern firing whenever you're doing anything.

All of your habits, ALL of them, are merely the sum of action bundles you've learnt to take given some context.

The wider implication here is: Action comes first. The “self” is what remains once those actions repeat.

Consequently, any and all advice given without a concrete set of actions to take, given a certain situation might as well be useless.

This flips the usual teaching model on its head

Most instruction tries to do this:

Teach the principle -> hope the actions follow

But the real path is:

Enact the actions -> notice they work -> stance crystallizes

Okay, but why should I care, @Alexanderr?

Because until you embody this truth, you’ll keep mistaking understanding for change -- and wonder why nothing sticks.

But I reckon this isn't news to a lot of you. You know. You know your habits define who you are, but you cannot seem to change them. You feel trapped by the parts of you that won't listen to reason. Like a ball endlessly trying to roll up a hill but mercilessly brought down by gravity.

See, I didn’t set out to write this as a drug thread. I set out to understand why change keeps undoing itself.

May I here introduce you to,

CREBINOSTAT

So, you think I'm introducing you to a miracle drug? I'm not. But here's why it's interesting anyway:

See, the problem for most people is that they can change any one of their moves any given day, the problem is that they don't stick. You go to the gym one day, but the action doesn't stick. You eat healthy one day, but the practice doesn't stick. Why is this?

Because evolution never wanted the (adult) human brain to be one that deviates from a stable state easily. It prioritized changing easily and changing quickly in early youth, but being efficient and stable nearing or upon adulthood. Meaning, if your current state is just enough to survive and reproduce, it's a-okay to evolution.

The implications here being that for you to change, meaningfully, you need to, (using our ball stuck on a U-shaped curve analogy) either:

1. Add massive energy

Trauma, ecstasy, crisis, obsession

-> brute-force shove over the ridge

2. Sustain repeated pushes

Slow learning, repetition, scaffolding

-> gradually reshape the basin

3. Change the landscape itself

Alter plasticity, consolidation, or stability parameters

-> same push now travels farther

Most adult change fails because people try #1 briefly or #2 inconsistently, while the system is actively defending #0: stability.

#3 is where Crebinostat comes in.

Crebinostat does not give the ball more force.

It does not create new hills.

It subtly:

- flattens the curvature

- widens the basin

- lowers the ridge height between basins

How? By lowering the bar for you brain to encode a memory, and thus not forget it.

What people don't understand about our biology and learning is that, forgetting is just as big a part. Your brain forgets all types of irrelevant noise (ex. random license plates) so you can learn or remember what matters (ex. mom's name).

Under normal conditions, the brain only locks in experiences that are clearly tagged as important; usually through strong emotion, novelty, fear, or consequence.

The problem is that there’s no immediate way for the brain to tell what will matter long-term. Your brain doesn’t know that skipping Chipotle is actually good for you.

All it records is a deviation from usual, considers it a fluke, prunes it during sleep, and moves on. Result? The memory trace "skip Chipotle" is never encoded (long term).

The claim here isn’t that one exposure creates a habit, but that a correct action is far less likely to be pruned by the brain -- so you’re not always starting again from square one.

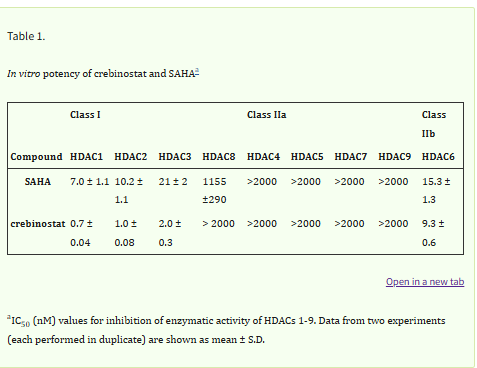

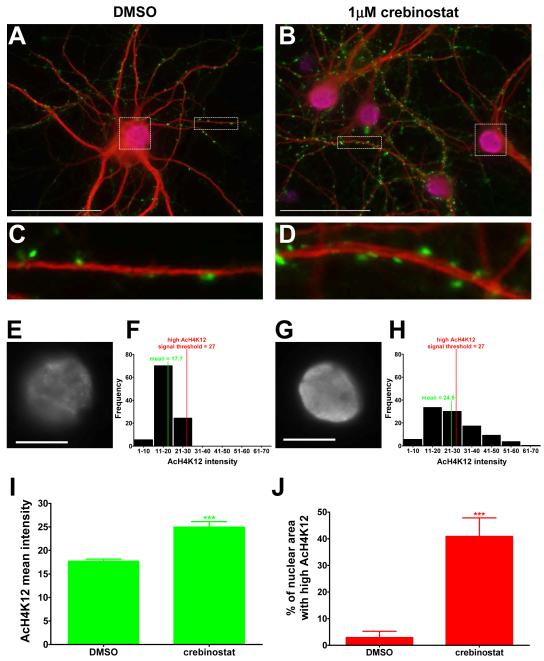

Crebinostat enhances memory by jointly lowering transcriptional thresholds (via potent inhibition of HDAC1/2/3) and stabilizing newly potentiated synapses during the early consolidation window (via potent inhibition of HDAC6), allowing weaker or shorter learning experiences to survive long enough for systems-level consolidation.

The exact division of labor between transcriptional gating (HDAC1–3) and cytoskeletal/synaptic stabilization (HDAC6) is still being worked out, but both converge on the same outcome: fewer new traces fall below the survival threshold.

I'll make a more expansive thread dissecting the research later.

The exact division of labor between transcriptional gating (HDAC1–3) and cytoskeletal/synaptic stabilization (HDAC6) is still being worked out, but both converge on the same outcome: fewer new traces fall below the survival threshold.

I'll make a more expansive thread dissecting the research later.

The failure mode for most people isn't in taking a different action, it's in not forgetting it immediately after. This is why Crebinostat is revolutionary.

As an example, there was a research study done. Researchers had a mice setup that was designed to test whether a weak learning experience could be converted into a durable long-term memory if the brain’s consolidation (remembrance) machinery was biased in its favor.

Task: A mouse briefly explores two identical objects, and 24 hours later memory is inferred if it preferentially explores a newly introduced object over the familiar one.

Key idea: They used learning examples (identical objects) that were deliberately too weak to produce long-term memory on their own.

Normally:

- the mouse experiences something once or briefly

- it learns it in the moment

- but forgets it by the next day

Can a drug make that same weak experience stick?

The answer: A resounding yes -- Crebinostat reliably turned a weak, normally forgettable object-recognition experience into a robust long-term memory.

Fass DM et al. Crebinostat: A novel cognitive enhancer that regulates chromatin-mediated neuroplasticity and enhances memory. Neuropharmacology (2013).

BUT @Alexanderr THAT'S IN MICE!!! WHERE ARE THE HUMAN TRIALS? HUH!? HOW'D WE KNOW IT WOULD TRANSFER?

Fairs, but without me going into the science of it all, given what we know about mice and humans... If Crebinostat failed to transfer at all, that would actually be more surprising than a modest, domain-limited benefit showing up in humans.

If I had to answer in one sentence, vividly, what sets Crebinostat apart from all other obscure or grey market drugs I've come across, it's that:

Crebinostat doesn’t push you to learn harder or feel more; it strengthens the brain’s internal scaffolding so that whatever you already did has a much higher chance of not collapsing overnight.

This is extremely rare because most drugs act on moment-to-moment signaling or arousal, whereas Crebinostat targets the slow, normally inaccessible molecular gate that decides whether learning is kept or discarded after the fact.

Examples of every day tasks people's brain generally forgets to store:

- Learning someone’s name once and actually remembering it the next day.

- Having a single good practice session stick instead of feeling lost again tomorrow.

- Adopting a simple habit or rule of thumb and finding yourself using it later without effort.

But why @Alexanderr, why do you post about an obscure, non-human tested research drug that would be inaccesible anyway?

Because for the first time (as far as I know) it's available to the general public. Although trough some peculiar means. I'll explain.

Someone I consider a friend is hosting a group buy for the drug, it's open until 31st of December. I make no money off of it, but I've been waiting for this opportunity to come by a couple years now [ever since I tried Vorinostat (similar, but less effective for these purposes)].

So I'd feel bad if those of you who are as interested as me in this entire bio-hacking stuff miss out on this (maybe once in a lifetime, idk) opportunity.

You can read and find more here.

Merry Christmas, fellas, I'll keep you updated on this pet project of mine.

THIS THREAD ISNT FOR IQCELS