Xangsane

squishy squishy!

- Joined

- Jun 11, 2021

- Posts

- 160,761

- Reputation

- 140,251

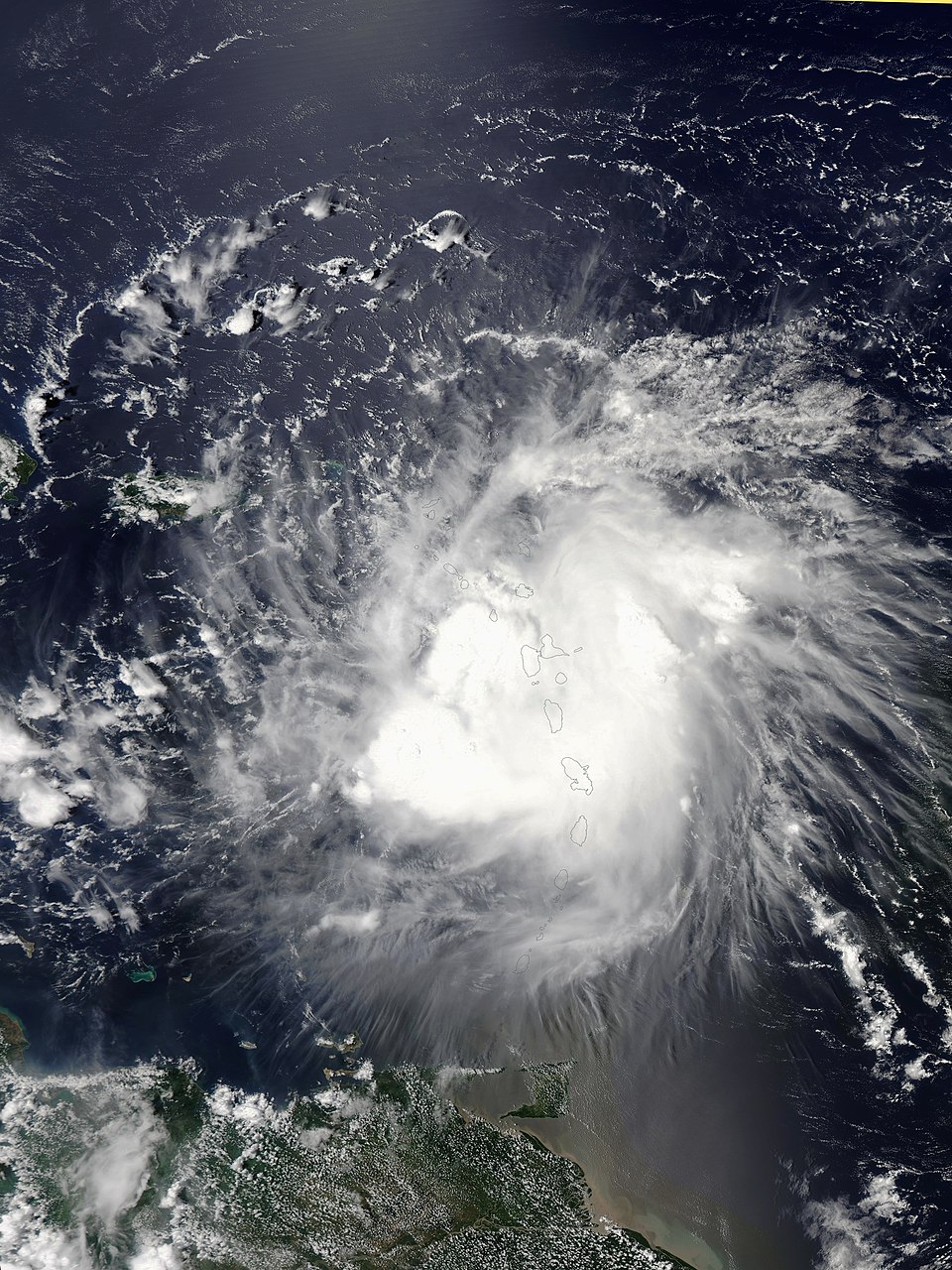

Models for Invest98L/Ernesto

Great OHC

Simulated IR

Extremely good pattern for RI in the deep tropics

Actually GFS is more south this run and stronger which is not what we want

HWRF moves him westward

Low ahh shear (which is good)

Long ahh path (might go ER on Bramladesh Pajeets in Canada)

Could mog

Likely a mogger

Could go ER on Bramladesh Pajeets

Invest 98L (which will become Ernesto) is ahead of schedule

But we don't know where he'd spray his coom

Great OHC

Simulated IR

Extremely good pattern for RI in the deep tropics

Actually GFS is more south this run and stronger which is not what we want

HWRF moves him westward

Low ahh shear (which is good)

Long ahh path (might go ER on Bramladesh Pajeets in Canada)

Could mog

Likely a mogger

Could go ER on Bramladesh Pajeets

Invest 98L (which will become Ernesto) is ahead of schedule

But we don't know where he'd spray his coom

Last edited: